Despite immense economic growth over the last decade, India ranks 65 out of 79 countries on the Global Hunger Index. India is exhibiting a phenomenon where the state has enough food for its 1.2 billion people, yet it struggles to feed a considerable amount of its population. Piles of food are rotting in warehouses, while approximately 43% of children under the age of five are chronically malnourished, and more than half of all pregnant women are anemic.

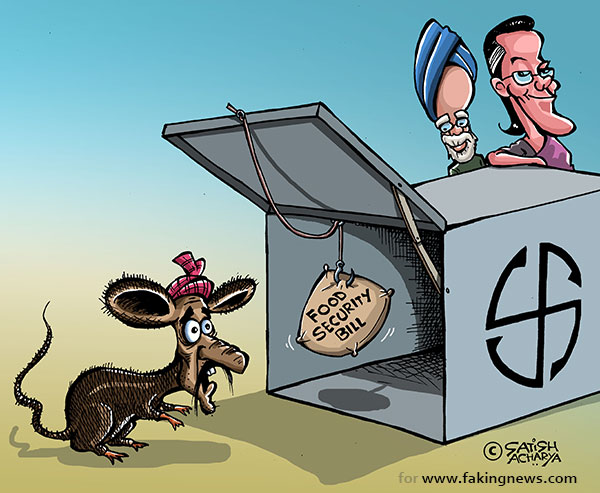

As a means to battle chronic hunger and malnutrition, the government of India has recently passed the Food Security Bill (FSB), which still requires ratification by parliament. The $22 billion program aims to make food a legal right by distributing subsidized food grains to two-thirds of the state’s population.

The FSB is a positive step towards providing nutritional security in India, but there are many drawbacks to the bill and it is far from a perfect solution.

The FSB proposes to supply 5 killograms of subsidized wheat and rice every month to nearly 800 million eligible beneficiaries. This covers 75 percent of the rural population, and 50 percent of the urban population; which is more than double the reach of existing subsidized food systems in India.

The food security ordinance should be great news for India, but it is being called one of the world’s largest welfare schemes. The Congress-led party is arguably using the FSB to win favour over rural voters in the national elections scheduled for next year.

The first issue is determining who is deemed eligible for the subsidized food grains. The bill states that it will compile a list of recipients who will receive ration cards. Identifying beneficiaries can be difficult because there is no set standard of measuring levels of poverty that is consistent across all organizations and institutions.

The second concern is the program’s goal to eliminate malnutrition. his is a problem that cannot be resolved simply by providing people with wheat and rice. More attention needs to be paid to providing adequate nutrition beyond the right to food. Malnutrition happens early on for many Indians and access to proper food and hygiene practices are critical in the first two years of life. The Right to Food Campaign explained, “If this opportunity is missed, the window closes, and it closes forever perpetuating an inter-generational cycle of undernutrition and deprivation.”

The third problem is the FSB’s lack of provision to address small and marginal agricultural farmers. If the government is the biggest buyer and seller of food grains, it could lead to a nationalization of agriculture. This would be problematic for many farmers who cannot sell their crops to the government-assured program. If the government is providing food at a lower cost, it will distort the market, resulting in lowered bargaining power for smaller agricultural farmers in the open market. In the end, a lot of farmers will suffer without any sort of protection.

The final drawback is concerning India’s notoriously-flawed Public Distribution System (PDS). The state-owned cheap food ration shops are problematic because it has a history of diluting the distribution of subsidized food. The leaky system has lost anywhere between 37 to 55 percent of food grains, which end up being sold in the open market at a higher cost. There is reason to fear that problems related to the PDS will intensify with greater amounts of subsidized food grains being distributed across India, however there have been positive results with PDS reform within the last few years.

In spite of these shortcomings, the FSB is not a lost cause. The Indian government seems confident and optimistic about the program, but it should be assessed for review and additional provisions.

For starters, there needs to be a way to reduce leakages and corruption with the PDS. This can be achieved by appointing a level of authority on the local level so that each individual business can be monitored frequently. It would also help in handling individual cases if any food grains are being sold illegally, and strict enforcement hand be dealt with accordingly.

Realistically, a single bill cannot address every single food-related issue, and the FSB is not a quick fix to solving India’s chronic hunger and malnutrition issues. It is important to address nutritional security from a comprehensive approach. If there were a combination of resources and access to essential services and education in addition to subsidized food grains, it would be a security net for the most vulnerable groups. As a result, the poverty rate in India can decrease, and the levels of hunger and malnutrition can drop considerably.