The core pillar of Finland’s foreign and security policy is military non-alignment. And yet, the Individual Partnership and Cooperation Programme (IPCP) anchors Finland in an integrated network of military defense. Currently, Finland participates in the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) Programme, the Planning and Review Process (PARP) and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC). Under that framework of cooperation, Finland has trained NATO forces, participated in peacekeeping missions in the former Yugoslav Republic and Bosnia-Herzegovina and currently Finnish soldiers are fighting alongside the Allied forces in Afghanistan. This cooperation in selected areas with NATO undermines its claims of non-alignment.

In early June 2012, Russian general Nikolai Makarov spoke before Finnish defense specialists criticizing Finland for its growing ties with NATO. Finnish Prime Minister Sauli Niinisto responded bluntly that as a free nation, Finland would determine defense and security policies on its own basis.

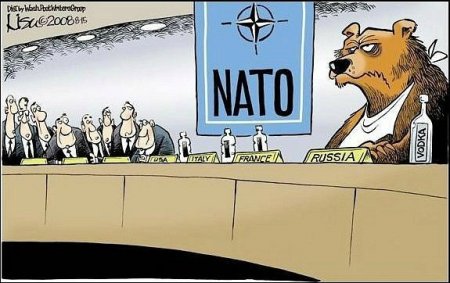

One year later on June 21, 2013, Russian President Vladimir Putin intensified Russia’s verbal intimidation campaign. In a meeting with President Niinisto, he said that, “The involvement of any country in a military bloc deprives it of a certain degree of sovereignty, and some decisions are made at a different level.” His counsel sharpened when he followed with the warning that militarization under the auspices of NATO would mean that, “Russia will take retaliatory measures.”

Finland is only one among several nations experiencing blatant hostility for its cooperation with NATO. To Russia’s’ eye, NATO’s dialogue with nations such as Sweden and Georgia reveals that NATO is expanding to Russian borders to tilt the geo-strategic balance in its favor. Yet, the question of NATO membership ultimately falls to Finland.

Finland adopted military neutrality as its security policy because of its geographic proximity to the Soviet Union and its vulnerability to the Soviet military influence. According to the advocates of NATO membership, Russia’s recent threats demonstrate that military isolation is outdated and dangerous, rather than a safe policy for a smaller country such as Finland. Membership would commit some of the world’s most powerful nations to defend their new ally under the requirements of Article 5 of the NATO treaty.

Critics argue that NATO membership should not be regarded as an end-all solution to Finland’s security. Article 5 has the potential to set in motion collective defense, but it doesn’t commit members to military action. It only requires members to take “such action as it deems necessary.”

History has taught the Finnish not to rely on the international community for aid in its defense or security. The Winter War from 1939 to 1940 against the Soviet Union left deep scars and engrained in the national memory the conviction that the nation stands alone. Coupled with distrust, is the fear that membership would weaken Finland’s military by diverting national defense resources to military conflicts across the globe.

The Finnish debate on NATO membership has waged for decades and Russia’s aggressive foreign policy was reinvigorated it. In reaction to the ambitions and influence of its powerful neighbour, Finland has carefully nurtured a cooperative relationship with Russia. For example, trade between the two nations is flourishing.

Finland has managed to work with NATO according to its interests and membership does not guarantee protection, but would incur new and substantial obligations. Russia’s threat however, compels Finnish policy makers to consider their strategy more carefully and NATO’s membership more seriously.