A precursor to this article, which outlined Bill C-44 and the Canadian Security Paradox can be found here.

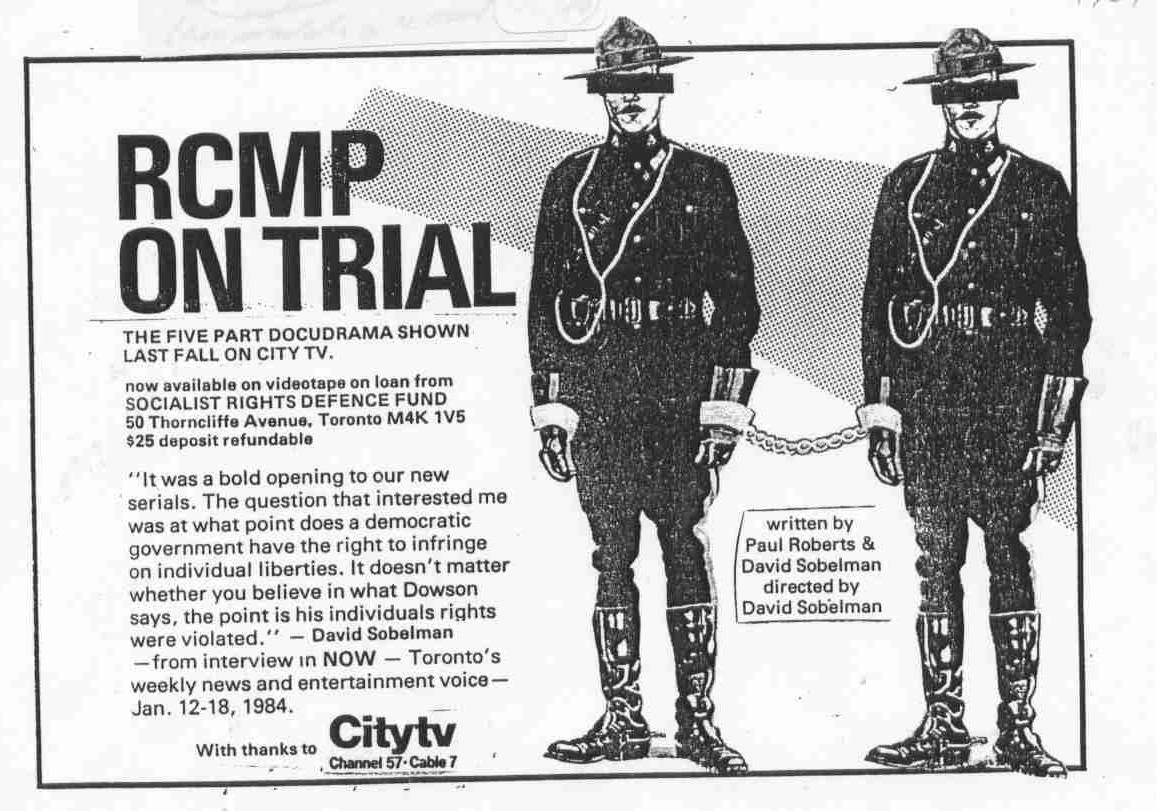

Perhaps ironically CSIS was created in 1984. Birthed out of the McDonald Commission, CSIS was introduced after allegations involving the intelligence branch of the RCMP were brought to light. These allegations included several break-ins; illegal opening of mail; burning down a suspected meeting place for Black Panther Party and FLQ members; forging documents; theft of the membership list of the Parti Québécois; and conducting illegal electronic surveillance. Canadians were startled by the magnitude of RCMP power abuses, and the McDonald Commission recommended that a separate security body should be created to separate policing from intelligence gathering.

Basically the equivalent of saying “you guys got caught screwing up so badly we have to eliminate your department and give those duties to a new agency.”

To protect against any future abuses, CSIS was initially designed to have two watchdogs: the Inspector-General, and the Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC). The SIRC reviews CSIS, and the Inspector-General used to provide reports on CSIS’s activities to the Minister of Public Safety, until the position was scrapped in 2012. The Harper Government claimed it was done as a cost-cutting measure, and that the reports that used to be done by the Inspector-General would now be done by the SIRC.

Unfortunately for most Canadians concerned about accountability, those in the intelligence community do not take the SIRC seriously. Former CSIS Director General Marion Bialek recently said that the SIRC’s “powers are very limited from an oversight point of view…There is no oversight process. SIRC is not an oversight body.” Not exactly reassuring support of our supposed primary oversight committee.

Former Chair Arthur Porter. Courtesy of Global News.

Former Chair Arthur Porter. Courtesy of Global News.

Aside from the structural limitations of the SIRC, many of the concerns over their ability to produce detailed legitimate annual reports stem from the SIRC’s inability to have consistent and dependable leadership. Former Chair, Arthur Porter resigned in 2011 amidst controversies involving fraud, and currently is running a ‘lucrative’ business in a Panamanian Prison while avoiding extradition charges for the multi-million dollar fraud scheme he is facing in Quebec courts. His successor, Chuck Strahl resigned this past January after it became clear that he was a registered lobbyist with Enbridge, the company tasked with the controversial Northern Gateway Pipeline. After Strahl’s resignation the SIRC staggered along with an interim chair, until Stephen Harper appointed Deborah Gray, a veteran of Conservative politics who played a major role in Harper’s 2006 campaign.

Wesley Wark, a professor at the University of Toronto and a visiting faculty member at the University of Ottawa, has argued that ministerial accountability over the spy agency has already been significantly eroded, and thus the dissolution of the Inspector-Generals office two years ago signaled further steps in the wrong direction. To be clear, the distinction between the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ directions in this context involves accountability, and the trend has been towards less accountability despite the growing evidence of corruption and abuses of power. Tasking a very limited review committee with the critical task of overseeing the growing scope of CSIS’s activities, without increasing their oversight capabilities is a recipe for disaster.

While contemplating the security of our country, it is important to reflect on the twin realities that currently underpin the Canadian security paradox. There is no such thing as perfect security, and the powers of prevention are often at odds with the guiding values of our democracy. Navigating this line in an increasingly complex world of security will be difficult, but it is possible. However, chasing dreams of total security at the expense of individual rights and freedoms undermines the ideals of contemporary Canadian society. If we are going to grant further powers to our security institutions we need to ensure that the oversight mechanisms are effective, robust, and free of the insidious corruption that has plagued them for years.