This week, we challenged the NATO Association of Canada’s Editors for their take on a thorny and challenging topic, namely:

Are sanctions an effective means of curbing illegal behaviour by ‘rogue state’?

Ditch the Logic

Arjun Singh

At its root, the question is empirical. Sanctions are effective only if, in cases where used, a desired outcome was achieved. Other tools of statecraft (e.g., the threat of force and diplomatic isolation) used alongside sanctions may be confounding variables and, hence, only those situations where sanctions were primary responses are appropriate for analysis. Variations in the international order compel a confinement of any assessment to the present period, i.e., post-2008, a unipolar world dominated by the United States, but racked by the legacy of the Great Recession, with weaker nations gaining strength.

In 2015, sanctions were effective against Iran – compelling them to sign the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and halt uranium enrichment. Certainly, Israeli military and U.S. cyber-action whipped them forward, but the gutting of Iran’s economy by unilateral U.S. sanctions caused widespread suffering, which Iran couldn’t tolerate. Similarly, in 2018, North Korea was compelled to negotiate and grant concessions on nuclearization after withering, repeated sanctions – at present, yielding the risk of famine in the country. While some may dismiss this case, since North Korea has not denuclearized, such dismissals are premature. The hardest sanctions take time to take effect – once resources of regimes are depleted, and the state reaches a breaking point. North Korea is currently along this path. Likewise, so is Russia – which, though it retains control of Crimea – has lost billions of dollars in energy revenues, and slowed its GDP growth by at least 2.5% since 2014. Though Russia continues to act counter to Western interests, sanctions have reduced the available resource they could use to act.

However, sanctions have not been effective in an equal number of cases. Despite their imposition, China persists with ‘re-educating’ Uyghurs; Turkey has bought the S-400 system; Bashar Al-Assad and Nicolas Maduro retain power in Syria and Venezuela, respectively; and, in Myanmar, the coup continues. Charitably, nothing has come of these efforts.

With these parameters, one finds that sanctions have, indeed, been effective – but not in all cases. More crucially, there is no consistent trend that can be drawn – to determine all situations in which sanctions are effective. It appears, thus, that a complex milieu of known and unknown factors, acting in an ad hoc situation, determine whether sanctions influence outcomes or not. If this is unsatisfactory, one should be rather pleased. The international system is complex and frustrating. Only war yields a sense of full victory.

Sure, sanctions are effective, but at what cost?

Eric Jackson

I was listening to a podcast from The Economist earlier in June. In this episode, the final segment – starting at 17:45 – highlighted an Iranian musician named Mim Rasouli. Unlike artists in the West who have direct access to paid streaming services, such as Spotify, Rasouli does not have this luxury. Most musicians living in Iran cannot use any mainstream media service because sanctions prevent Western companies from engaging in commercial relationships with Iranian entities or individuals. Since Spotify pays its artists, this would violate U.S. sanctions. Therefore, Rasouli cannot make a living from his work.

Another Iranian example, this time from BBC, details the effect of the sanctions on a young boy named Mohammed. Doctors believe that Mohammed suffers from a rare genetic disease that causes him to be too weak to lift his school bag. When his mother took him for a test, the neurosurgeon charged $1000 – a sum she could not pay. In addition, U.S. sanctions imposed at the end of former President Trump’s tenure caused extreme inflation in Iran’s economy. The World Bank found that meat products in 2019 were 116% more expensive, with rural populations disproportionately affected.

The moral of the story from the Iranian case? We cannot consider sanctions to be an effective means of controlling ‘rogue states’ when the consequences of those sanctions affect innocent bystanders.

From a holistic perspective, credit must be given where credit is due. Sanctions on Iran in 2015 incentivized President Hassan Rouhani to limit Iranian nuclear activity in exchange for economic freedom. A similar scenario occurs today where President Biden is considering lifting sanctions from 2019 as part of negotiations to reinstate the Iran Nuclear Deal.

However, this ‘holistic perspective’ inappropriately overlooks the human cost associated with sanctions. For example, earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, Iran urged the U.S. to lift sanctions that hampered Tehran’s response to the health crisis. The struggle with international politics is that it’s very easy to become fixated on achieving the end goal without fully considering the consequences of one’s actions. Despite achieving foreign policy goals, the Iranian case reminds us that sanctions exact a significant human cost on unintended targets.

Sanctions: A Blunt Instrument

Juliana Schneider

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Western powers have enjoyed a monopoly when it comes to the practice of international relations and the rules-based order. Western states have been able to yield this power globally thanks to their growing and thriving economies, social structures and military capabilities which have placed them at the centre of anything from international communication networks to trade. In this time, these actors have become accustomed to this power structure, particularly when there were few other international players that had the capacity to meaningfully challenge them. In this structure, sanctions could be leveraged because of the clear dominance of Western powers and their ability to coordinate international politics. Weak states, with little bargaining power or international influence remained dependent on stronger states and consequently, the threat of sanctions held a disproportionately negative impact on them. In the last several years, certainly the last decade, this international power structure has slowly shifted, most notably towards China but also Russia and other growing international players. Some of these actors have been increasingly bold in their international actions, such as the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the ensuing sanctions seem to have done little to sway this belligerent. Moreover, as such sanction regimes are proven to be relatively ineffective in dissuading international violations when the risk is worth it, it not only emboldens other potential rogue states by showing sanctions can be survived but it also indicates the deterioration of sanctions as diplomatic symbols. As Richard Connolly writes, “Sanctions are what you do when you don’t know what to do” (Connolly 2014, p. 2).

Sanctions have the means to be effective so long as the countries imposing them can exploit power gaps either individually or as a group. They may also be effective if countries are willing to impose harsh sanctions whose repercussions are most strongly felt by the general population of the targeted country, rather than the elites responsible for political decisions. Moreover, in such cases, the imposing country must also be willing to absorb any shocks of sanctions on its own economy. As new international powers rise that disrupt the current global power hierarchy, sanctions may no longer be sufficient in curbing rogue states. This is an emerging challenge for key international powers that must be addressed in the coming years if the international rules-based order is to be preserved.

Works Cited

Connolly, Richard, “The Effect of the Ukraine Crisis on the Russian Economy,” European

Leadership Network, 2014.

Sanctions regimes need to be broader to have an impact on their own

Griffin Cornwall

Economic sanctions regimes are often levied against ‘rogue states,’ in an attempt by members of the international community to push these actors into curbing disruptive actions or reversing negative policies. While sanctions often do have an impact on their target, some longstanding sanctions regimes have failed to modify the behavior of the target significantly as sanctions regimes can fail to strike deeply enough at the core of the targeted economy or sanctioned states turn to sympathetic allies with stronger economies and a willingness to continue trading.

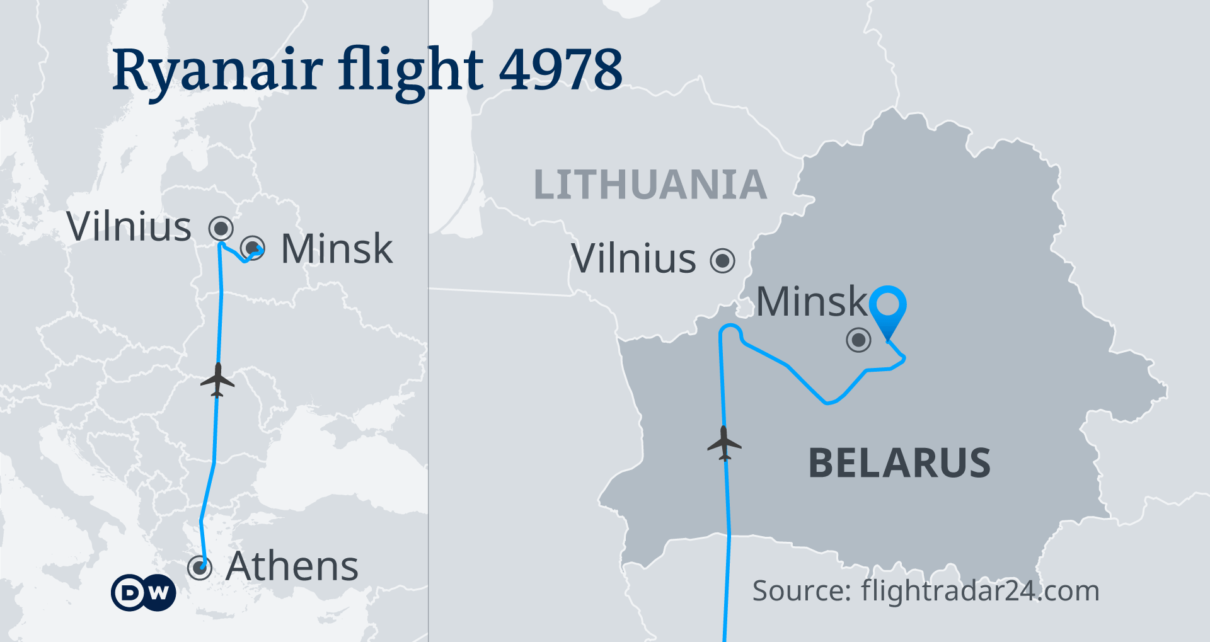

A recent example of ineffectual sanctions has been the European Union-led effort to sanction Belarus for its poor human rights and electoral freedom records. Beginning in 2004, the bloc has placed successively tighter sanctions on Belarus targeting individuals with travel bans and asset freezes for their involvement in unfair elections and acts of repression against civil society, progressing to a full arms embargo and an export ban on “goods for internal repression.” Despite President Alexander Lukashenko remaining in power by continuing to exploit a series of unfair presidential elections, the EU actually relieved some sanctions pressure in 2016 as Lukashenko sought to improve relations between his country and the West. Regardless of the changing sanctions situation Belarus has continued to maintain healthy international trade partnerships, primarily with Russia but also with a variety of its European neighbours inside and outside of the EU.

With the fallout from the crackdown against the 2020 Belarusian presidential election and the dramatic diversion of a Ryanair flight to arrest dissident Roman Protasevich, again souring relations with the West, new sanctions are coming into effect. In a recent interview, former Belarusian government official turned dissident Anatol Kotau, called for harsher sanctions against Belarus claiming that heavy sanctions against key exports would be the only effective way of impacting the Belarusian economy strongly enough to break President Lukashenko’s firm grip on power. On June 24, 2021 for the first time, the EU implemented the kind of harsher sanctions Kotau had suggested would, barring Belarus’ main exports, curtailing its access to European financial markets and upholding a ban on Belarusian air carriers entering Europe. While the full effect of the sanctions have yet to be felt it would seem that they may finally have a deeper impact.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.

Cover Image: Ryanair flight 4978 flight path over Belarus. Source: flightradar24.com via DW.com.