On June 24, Turkey witnessed two historic elections that led to the formation of a new legislature and a fresh presidential election. More importantly, this date marked the first elections that decided a president with new powers outlined in a new constitutional amendment. The Turkish people elected Recep Tayyip Erdoğan with 52.59% of the vote and saw a record 87% turnout. Erdogan’s newfound powers are supported by his party gaining a majority in the Turkish legislature; although, with its diminished power, the legislature is not very necessary to accomplish his political objectives. This early election has decided a new direction in Turkish

[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Emboldening Erdogan with these new powers means Turkey is on a path towards autocracy that sets the country apart from its NATO allies[/perfectpullquote]

politics. Even though the practice of elections points to democracy and legitimacy in leadership, the truth is that its democracy is far from free and fair. Instead, emboldening Erdogan with these new powers means Turkey is on a path towards autocracy that sets the country apart from its NATO allies.

When considering the course of the campaign, these results are not surprising. From the very beginning, Erdogan and his allies closely controlled the election to ensure his party and image remained favourable for the majority of Turks both within the state and abroad. The election occurred 18 months earlier than scheduled and under a state of emergency that has been extended seven times after it was implemented in 2016 in response to a failed coup attetmpted against the president. During this election, Erdogan’s office enjoyed control over rallies, ballot boxes, and airtime for campaigning on Turkish networks. State broadcaster TRT allotted 181 hours of airtime for the incumbent, a far cry from opponent Muharrem Ince’s 15 hours, and imprisoned Kurdish candidate Demirtas, who was given only 32 minutes. Additionally, electoral reforms gave government officials greater control over ballots rather than party officials, and stamps that aim to prevent fraud were no longer required to validate votes. Under these conditions, the success of Erdogan and his party for mobilizing support that saw him re-elected is unsurprising.

What is surprising is the support Erdogan most likely received from expatriate Turkish community living across Europe and around the world. The importance of support for Erdogan from Turkish people living outside of the country is clear from the lengths Erdogan has gone to appease the base in addition to this group’s voting patterns. Erdogan and his party included a platform directly pertaining to the interests of Turkish expats. Erdogan even held a rally in the month ahead of the election in Sarajevo, spreading his message and trying to reach the over one thousand Turks living in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although they no longer live in the country, and many are second and third generation citizens of foreign countries, Erdogan saw the value of their support and ensured his message aligned with theirs.

Although results pertaining to how Turks voted overseas have not yet been released, past elections including the 2017 referendum and 2015 general election indicate expatriate Turkish voters generally favour Erdogan and support him at the polls. As this referendum granted greater authority to President Erdogan, it is logical to assume that those who vote in support of extending Erdogan’s powers would vote to elect him as President and thus, cement his newfound powers. Of the 1.4 million expatriate Turks who voted from abroad during the constitutional reform referendum, 59 percent voted in favour, with the largest support coming from Western European states including Belgium (75 percent), France (65 percent) and Germany (63 percent). As Turkish expatriates comprise five percent of the electorate, this base is significant in securing Erdogan’s victory and lucrative for a leader seeking to cement his power. While there is no singular reason why such support for Erdogan exists among expatriates, it is evident that this group in favour of an emboldened President form a key base, especially as voters in Turkey become more disenchanted with the current government in a declining economy.

What makes this pattern more curious is that in general, voters of Turkish descent in these states support more ideologically liberal candidates in domestic elections. While 21 percent of Turkish-German dual nationals supported Turkey’s constitutional referendum, German Turks generally voted for the liberal SPD party, at a rate of 40.1 percent. This key constituency that serves as a decider for the direction of Turkish democracy, and its pivot away from this democracy, vote to maintain those democratic structures at home. This is significant as votes from the Turkish diaspora might have a decisive meaning, and thus are a valuable base Erdogan can use to maintain and further extend his own powers in Turkey.

In light of scandals that have raised questions surrounding the legitimacy of elections around the world, our democracy seems more fragile than ever before. As such, ensuring the results of an election are legitimate and based on the true will of the people rather than a result of manipulating the perceptions of susceptible groups of people to benefit the ambitions of a strongman. It’s unfair both to Turkish democracy and to the international world order Erdogan’s expanded powers undermine.

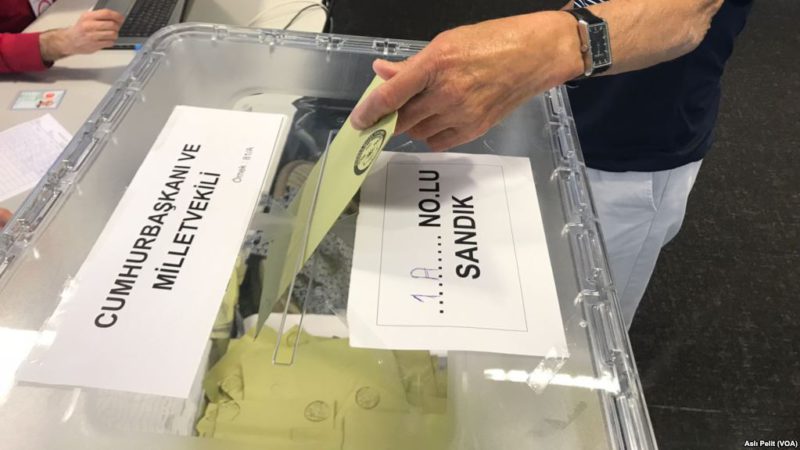

Photo: A vote being cast for the Turkish presidential and parliamentary elections of 2018 by Asli Pelit via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.