The collection of information on enemies, or potential enemies, can be traced back to the battles of antiquity, and even the Chinese strategist Sun Tzu. New technologies and new methods of keeping and hiding information, however, have vastly changed the intelligence cycle and the way in which intelligence can be gathered, both against state institutions, as well as individuals.

The Changing World of Intelligence

Where intelligence was once much more crude, comprised primarily of observational skills, recording the exact location of an enemy on a map and reporting it to one’s commander, it is now so complex that it requires multiple steps and particular skillsets, but also so simple that it can occur from the other side of the planet. The Traditional Intelligence Cycle was developed by the Central Intelligence Agency in order to effectively outline the steps in which intelligence could be gathered and used. As many in the intelligence community have discovered, this system does not effectively incorporate the constant change that occurs within the system itself. More specifically, it does not account for the rapid influx of information that can occur using new technologies and techniques, such as data mining.

As a result of this influx, it becomes increasingly difficult for any organization, including the CIA, to effectively analyze the incoming information. This inability to effectively analyze information means that important cues are missed. Even in the pre-9/11 intelligence gathering community important information was unable to be effectively used, even though it was available, which prevented any potential deterrence action. As the post-9/11 intelligence communities of most states have adopted more rigorous intelligence gathering mechanisms, more intelligence information is now available globally than has been the case in previous decades. The result is not necessarily positive.

The US and Intelligence Gathering

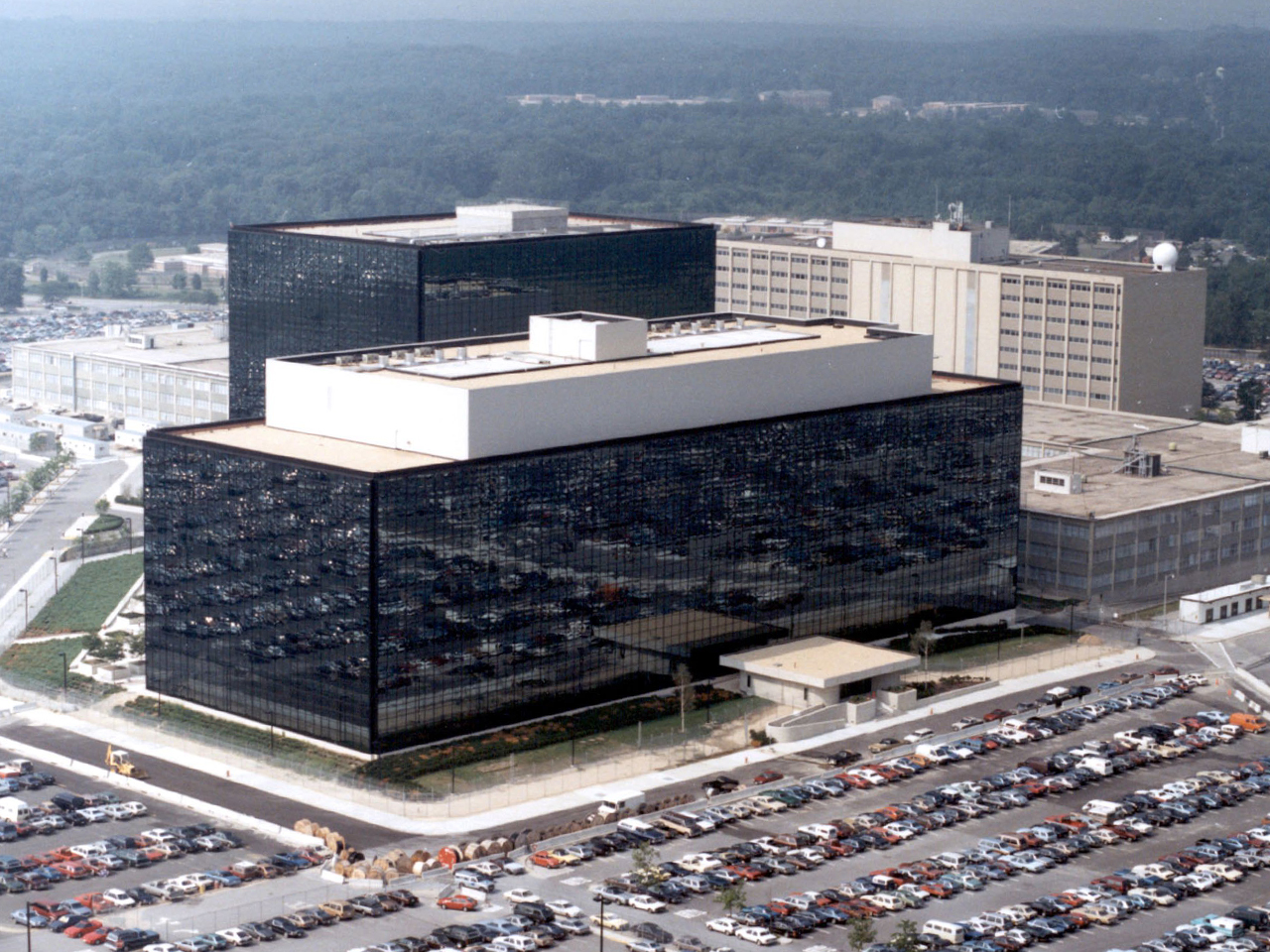

Since 9/11, the US government has worked diligently to ensure that terrorism does not again target the US or its allies. One of the most prominent actions was to pass the USA Patriot Act of 2001, only a month and a half after following the attacks. This Act, which hopes to “unite and protect America by providing appropriate tools required to intercept and obstruct terrorism” provides the US government with a number of “authorities” to collect information, in the name of protecting the American people.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”475″ imgsrc=”http://www.flashrouters.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/nsa-headquarters.jpg” captiontext=””]

Two important conflicts arise: the first is indicated by the revelation of PRISM program by Edward Snowden indicates that the US government is not only spying on international non-state actors, but also on US citizens, internal non-state actors, and therefore impinging upon the civil liberties that the US government claims to be protecting. This revelation calls into question whether the US government is still protecting the people of the US from terrorism, or is the government protecting itself in the form of silent terrorism? The second major conflict is pragmatically the most important from an intelligence community perspective: the US government is collecting too much information, and, just as before 9/11, is unable to effectively analyze the data, and therefore unable to effectively use the data in countering terrorism, at home or abroad. As a result, the threat posed by cyber intelligence programs such as PRISM is not only one in which personal privacy no longer exists, but also that the intelligence community is not able to effectively provide warning of potential threats. As a result, the most important question that must be asked is whether or not the cost is worth the benefit.

Canada’s Cyber Intelligence Model

As cyber intelligence continues to grow, and additional PRISM-like situations appear across the globe, Canada must also consider its own role in the collection of intelligence in cyberspace. Although Canada’s intelligence community is much smaller than that of the US, and focuses primarily on security screening, there is indication that Canada does take cyber threats seriously, and hopes to protect critical infrastructure from cyber attack. In doing so, CSIS follows the traditional intelligence cycle, with specific direction from the Government of Canada. While this is an understandable approach, particularly given the much smaller amount of information that CSIS must analyze, allegations that Canada’s Defense Minister Peter MacKay approved a project similar to PRISM in Canada indicate that this intelligence cycle is perhaps not the most effective. Instead, a more comprehensive intelligence cycle, such as Treverton’s “Real” Intelligence Cycle, may be more able to adequately provide the necessary feedback to increase effectiveness. Without the ability to consistently match intelligence data to the given objectives, it becomes nearly impossible to find anything significant within a particular dataset. An increase in the amount of data that is developed through programs such as PRISM, makes an already daunting task increasingly difficult for intelligence analysts.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”475″ imgsrc=”http://www.cbc.ca/includes/promos/promo/images/mackay-cp-9765437-584.jpg” captiontext=”Defence Minister Peter Mackay is alleged to have approved a program similar to PRISM.”]

While the ethical and legal questions regarding PRISM will continue to persist, it is also necessary to consider the costs of a program that will allow any agency to acquire such a vast amount of information. Simply having information does not allow the information to be useful. Although cyberspace does allow for increased access to information, which has the potential to provide a better understanding of one’s security circumstances, it does not allow for that information to be properly analyzed. In order for a program, such as PRISM, to be practical, some important advances in data analysis and prioritization must first take place. Once this becomes practical, the current ethical and legal debates will become immediate necessities, rather than distant speculations.