On November 15, Serbia signed an agreement with Azerbaijan to purchase 400 million cubic metres of natural gas per year beginning in 2024. The agreement comes simultaneously with the inauguration of a gas-pipeline interconnector between Serbia and Bulgaria, having a capacity, on the Serbian side, estimated at 1.8 billion cubic metres per year (bcm/y).

The volume is equivalent to about 60 percent of Serbia’s annual gas needs. It is expected that purchases from Azerbaijan will more than double in 2025, before reaching the pipeline’s full capacity in 2026. This significant development in Azerbaijan’s increasing contribution to the region’s energy landscape allows Serbia to diversify its gas supplies, reducing its dependence on Russian gas.

The newly completed pipeline runs from the town of Novi Iskar in Bulgaria to the Serbian city of Niš. It will enable Serbia to source natural gas from Azerbaijan as well as from the liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in the Greek port of Alexandroupolis. The European Commission contributed €49.6 million to construct the interconnector as a Project of Common Interest. Additional funding came from the European Investment Bank and Serbia itself.

European Energy Trends and Policies

This deal is part of a broader shift in European energy policy, as countries seek alternatives to Russian gas in the wake of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Azerbaijan’s role as a gas supplier is growing in importance, with its exports to Europe set to increase from just over 8 bcm in 2021 to around 12 bcm this year. Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev indicated that his country is on track to double its gas supplies to Europe to 20 bcm by 2027.

Natural gas demand in Europe grew from 380 bcm in 2003 to 520 bcm in 2022. Russia, before re-inaugurating its war of aggression against Ukraine, was a long-standing provider of European gas imports, representing variously one-third and one-half of total imports over the past two decades. The figure in 2022 was close to 45 percent of total imports, although this number is expected to fall in 2023 and beyond. Yet while the EU imported 57 percent of its natural-gas consumption in 2007, by 2021 this figure had increased to 97 percent.

In the second half of 2019, European and international financial institutions adopted policies under which they renounced further sponsorship of the construction of international oil and gas pipelines. These institutions included the European Investment Bank, the European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Commission’s process for designating Projects of Common Interest that would be sponsored by the Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA, now called the European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency or CINEA).

The last of these was specifically given the mission by the European Union to “deliver the European Green Deal through high-quality program management.” Some small exceptions remain for so-called “interconnectors” that, as the name suggests, connect existing pipelines amongst themselves. One example is the so-called Solidarity Ring pipeline in Central and South-East Europe (CSEE), formerly known as the Eastring project when it was first introduced in 2015. A feasibility study co-funded by the European Commission was completed in September 2018 with positive market-testing results.

BRUA and the Solidarity Ring

Another project, currently on hold, is the Bulgaria–Romania–Hungary–Austria (BRUA) pipeline project. It and the Solidarity Ring are distinct but related projects sharing the same broader goals of regional energy cooperation and integration. These goals are contextualized by the need to strengthen the continent’s energy independence and resilience by diversifying gas sources and reducing dependence on single suppliers.

The BRUA pipeline is a straightforward natural gas pipeline project, whereas the Solidarity Ring initiative—which has acquired the acronym “STRING” (considered by some to be dull and unimaginative)—focuses on upgrading the transmission network systems in the participating countries so that European customers may receive additional gas deliveries from alternative sources, particularly Azerbaijan.

Phase 1 of the BRUA project was completed in October 2020, comprising a 479-kilometre segment entirely within Romania at a cost of €423 million. It has a two-way transport capacity of 1.5 bcm/y to or from Bulgaria and 4.4 bcm/y bi-directionally from Hungary. Earlier this year, the Hungarian foreign minister signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Azerbaijan foreseeing eventual Hungarian purchases of that amount from SOCAR.

BRUA Phase 1 is operational, whereas Phase 2—which foresees extending the pipeline from Hungary to Austria—is proceeding by fits and starts, currently with a nominal completion date planned by 2024. Phase 2 has had problems and was postponed, primarily due to uncertainties around new Romanian gas production from the Black Sea offshore. Phase 3 would then involve expansion within Romania with a further Black Sea connection. It is in the planning stage and has no confirmed timeline.

The Solidarity Ring is a separate initiative from the BRUA project and has a broader scope, encompassing more countries, with an estimated cost of around €730 million. Also differentiating it from BRUA are the fact that its completion is anticipated by the end of 2026, as well as the fact that it has the necessary EU financial support.

The Eastring project had a projected capacity of 20 bcm/y scalable up to 40 bcm/y, connecting Slovakia with the external border of Bulgaria, through the territory of Hungary and Romania. Earlier this year, on April 25, the natural gas companies of those four countries (and/or their gas distribution subsidiaries) signed a MoU with the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijani Republic (SOCAR).

The Solidarity Ring first stage envisions deliveries of 5 bcm/y, later to be increased. In line with the foreseen 9.5 bcm/y ultimate capacity, Azerbaijan estimates deliver that quantity of its own gas to CSEE, in the first instance through the Solidarity Ring network. These quantities would arrive in Europe via the existing Southern Gas Corridor.

Conclusion

Serbia is not an EU member, but its gas deal with Azerbaijan shares the common goal of diversifying energy sources while leveraging the Bulgarian gas network’s existing infrastructure. The agreement with Azerbaijan arises from Serbia’s autonomous efforts—which are independent of the Solidarity Ring initiative—to diversify its gas supply sources. These efforts happen to mesh with Azerbaijan’s expansion of its gas exports to various European countries.

The Azerbaijan–Serbia gas deal and the Bulgaria–Serbia pipeline are related to the overarching European goal of diversifying gas sources and routes, but they are not directly related to either the Solidarity Ring or the BRUA project. To the degree that it aligns more with one than the other, this would be with BRUA. The new pipeline between Bulgaria and Serbia, transporting gas from Azerbaijan, is not officially part of the BRUA project.

The Bulgaria–Serbia pipeline falls into the framework of ensuring a more diversified energy supply in the Balkans by improving energy connectivity. As such, despite not being a direct part of the Solidarity Ring initiative, it aligns with the broader European energy-diversification strategy, including projects like the BRUA pipeline and the Southern Gas Corridor.

To recall, the Solidarity Ring is a specific initiative focusing on creating a transmission corridor amongst Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Slovakia by upgrading their transmission networks. This project increases the EU’s security of supply of natural gas, particularly in the CSEE countries, by diversifying their sources of supply.

The BRUA project, given its route and the countries involved, has more direct geographic significance and strategic relevance to Southeast Europe and the Balkans, than to Central and Eastern Europe, on which the Solidarity Ring orients its attention. Also, in the broader scheme of things, the BRUA project has a more direct focus on the diversification of sources and routes.

At the same time, their relationship is synergistic. The BRUA pipeline connects with the Trans-Balkan Pipeline, which is in turn a key component of the Solidarity Ring. This physical interconnectivity could later allow for a flow of gas between the two projects.

In a more general “philosophical” sense, both the Azerbaijan–Serbia deal and the Bulgaria-Serbia pipeline align, therefore, more closely with the broader objectives of the BRUA pipeline project than with the Solidarity Ring initiative. This is also because Serbia’s energy strategies, including its deals with Azerbaijan and its pipeline project with Bulgaria, are more directly related to the Southern European and Balkan energy landscape.

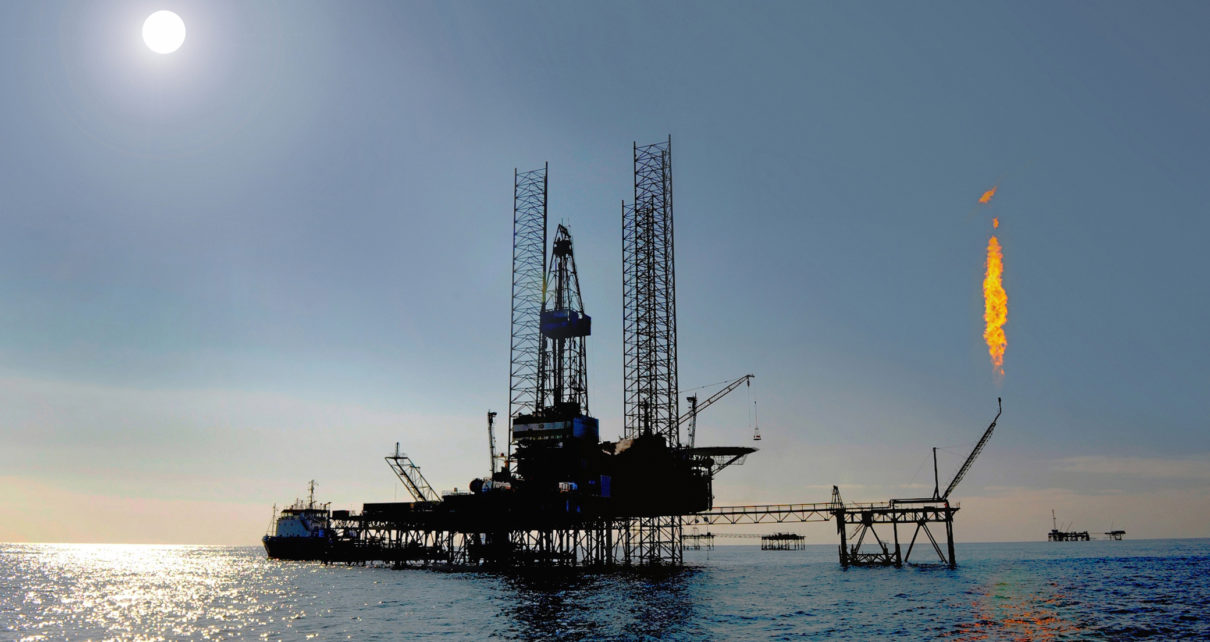

Photo: ‘Jackup rig in the Caspian Sea’ by Dragon Oil / www.dragonoil.com. Licensed from Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.