Large increases in uncontrolled migration, much of it involuntary, have figured prominently in recent political discourse on both sides of the Atlantic. The European Union (EU) has been confronted with a crisis due to an influx of refugees and migrants mainly from the conflict zones of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), as migration flows more than doubled in 2015. This on-going refugee crisis has triggered a broad range of responses within the EU, all of which are not surprising given the diversity amongst the 29 member-states. Nevertheless, it may be argued that the negative discourse stemming from EU discussions and policy measures have one fundamental trait in common, namely, the notion that such a refugee crisis is a perceived security threat to both the individual states and to the Western world as a whole. This process of addressing an issue with an elevated degree of urgency in order to legitimize extraordinary action has been developed under the label of the securitization theory, as advanced by the Copenhagen School of security studies. Certainly, this securitization of refugees has been noted within the institutional framework of the EU, however the measures taken by individual states pose a challenge to the unity of the EU itself.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“The unilateral re-establishing of border controls within the EU is not a long-term solution to the current refugee crisis…. [I]t will only move pressure points from one border to another, thus resulting in an increase in the securitization of refugees.”[/perfectpullquote]

Still to this day, most of the measures implemented by the EU and its member-states do not go deep enough to address the symptoms and unintended consequences behind the refugee crisis. This predominantly concerns a lack of effective action on reformulating the sharing of protection for refugees, and in turn, the sharing of the burden between member-states that goes beyond what is stipulated in the current Common European Asylum System (CEAS). Instead, it can be argued that member-states, and the EU as a whole, have given priority to securitized asylum and border policies that are driven by a perceived refugee-security nexus and the interests of individual states. Such policy priorities have become “security-driven (home affairs) and military concerns focused on the implementation of border controls, the return and re-admission of irregular migration flows, and the fight against refugee-smugglers and terrorism.” Still, events such as the terrorist attacks of the past several years in the EU, which tear away at the very fabric of European integration and stability, should not be taken as an opportunity to dismiss EU member-states’ initial commitments towards the legislative and policy measures already adopted in the scope of the European Agenda on Migration and the CEAS. These fears of a dramatic increase in potential terrorists infiltrating refugee flows to conduct heinous acts of terror within the borders of Europe that seek to disintegrate the Union are misplaced.

The EU has managed to muddle through an uninterrupted string of crises during the last decade, and the refugee crisis may be no different; yet, muddling through is no solution. Like every policy course, the EU has its own limits, and these are certainly being tested as never before. The EU policy responses, both unilaterally by member-states, and in cooperation with third party states have predominately lacked a multifaceted political and military approach. By ‘going-it-alone’ to address this crisis, member-states are taking measures that are driven by national security, which is jeopardizing the overall security of the EU and preventing a wider, more unified approach to mitigating or even resolving the crisis.

The unilateral re-establishment of border controls within the EU is not a long-term solution to the current refugee crisis. Rather, it will only move pressure points from one border to another, thus resulting in an increase in the securitization of refugees. This process will only create further “divisions within the EU, with national interests being prioritized ahead of a common plan for all the member states.” The growing threat on the EU’s southern flank – the Syrian civil war and mass migration – constitutes not only a geopolitical, but also a humanitarian challenge that is straining EU and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member-states’ political cohesion and institutions. As such, the refugee crisis continues to have complex security implications for Europe as a whole and for the overall transatlantic relationship.

Although the EU has been charged with leading a response to the refugee crisis, it is becoming increasingly clear that the current mode of operation of the European Commission, and the EU as a whole, is incapable of responding in a timely or appropriate manner. What is needed, then, is a comprehensive approach between the EU and NATO that seeks to address the EU’s disintegration and insecurity that is arising not just from a spectacular influx in migration, but from the unilateral over-securitization of such refugees and borders.

The severity of the crisis for the EU lies in the fact that its root causes are outside Europe, yet it must be made clear that solutions to mitigating, or even resolving the unintended consequences associated with the crisis rests within Europe, not outside it. The controls currently being implemented to address this crisis are disproportionate and have proven ineffective in mitigating the flow of refugees; if anything, they have made the EU more insecure. Accordingly, the solution rests in increasing European defence capacity. The EU must strengthen and regulate its flanks, not only to the East, but also to the South of the Union. What is required is a unified, robust EU and NATO policy: let refugees in, but regulate the movement at the external borders of the Europe Union. In order for this to be plausible, the EU must establish a closer working relationship with NATO. Leaders must come to the table with more on their minds than purely national interests; indeed, now is the time for consideration of what the meaning of ‘European Union’ truly is.

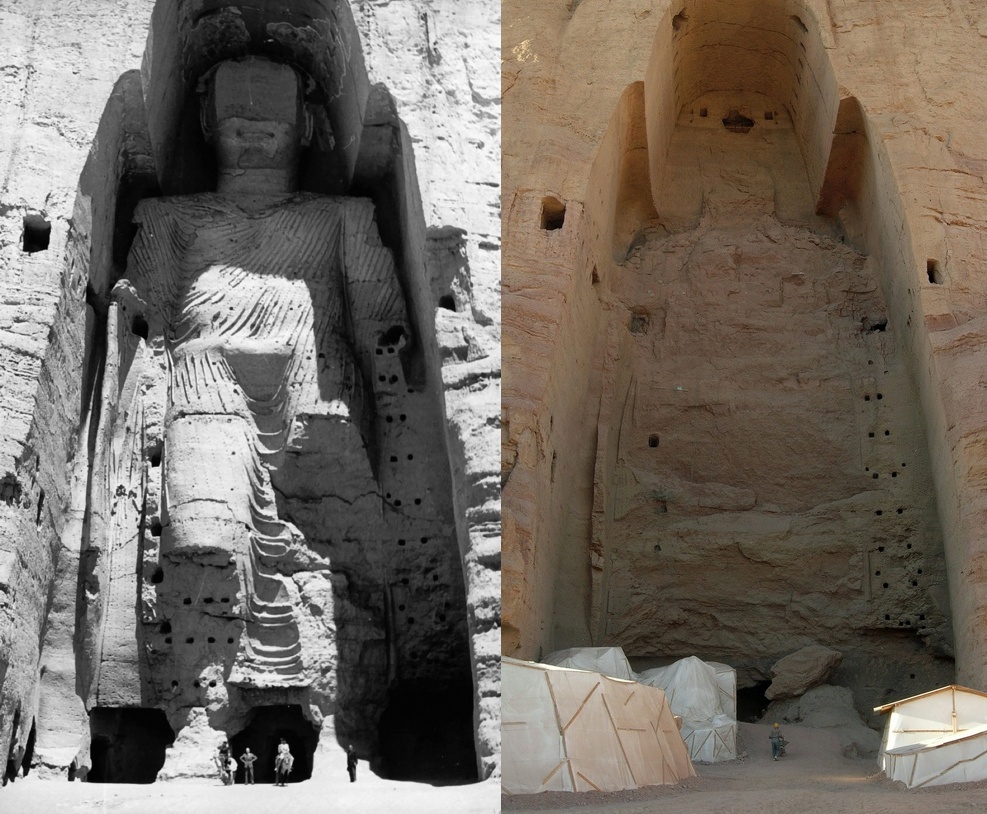

Photo: Syrian refugees protest at the platform of Budapest Keleti railway station. Refugee crisis. Budapest, Hungary, Central Europe (2015), by Mstyslay Chernov via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC 4.0 International license.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.