[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=” http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/73/Shanghai_Five_Leaders_2.jpg ” captiontext=” The Shanghai five”]

A month has passed since the Shanghai Cooperation Organization [SCO] concluded its yearly conference, leaving much to anticipate in the upcoming period as member states reaffirm their commitments to increasing stability in Central Asia. The SCO 12th Annual Summit, held in Beijing from June 6-7, focused on both counter-terrorism efforts and the containment of extremism, together with pledges to enlarge regional trade relations. While these themes are in accordance with the founding goals of the SCO, this year’s talks garner significance internationally with the announcement of the recent admittance of Afghanistan. The talks resulted in a blueprint of developmental objectives for the next decade, a consequential shift in the priority and focus of the organization.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization was inaugurated in 2001 as an intergovernmental institution by the states of the Shanghai Five – China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan – plus Uzbekistan. In addition to the founding members, the SCO is also comprised of observatory positions, which include India, Iran, Mongolia, Pakistan and now Afghanistan. The organization is principled on the grounds of mutual peace and security, and has been utilized as a framework to promote economic ties and cultural understanding. Beyond this, the SCO has stood in strong opposition to foreign military presence in Central Asia arguing that the involvement of armed forces represents a threat to regional and global stability.

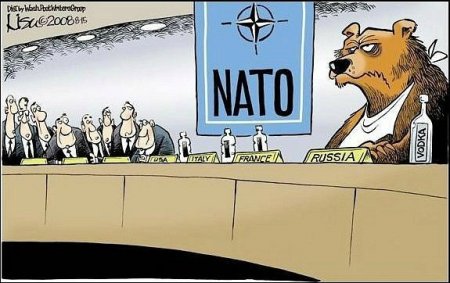

The NATO of the East

The SCO’s largely security driven agenda has given rise to speculation that the organization has evolved as a counterbalance to NATO in the East. Chen Yurong of the China Institute of International Studies stated “The combat against the ‘three evil forces’ of terrorism, separatism and extremism remains the major task of the SCO since it was founded. There is no talk of transforming the SCO into a cohesive military alliance like NATO.” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Weimin has echoed a similar claim, arguing that the charter of the SCO has determined that the nature of the ‘non-alliance’ organization is based on openness and non-aggression towards any country or institution.

Yet with the SCO’s expansion of its membership and recent extension of its focus towards development, the organization has gained political influence. The increased leverage it has internationally has triggered speculation regarding the future of the SCO and its capacity in the global arena. As two principal states of the SCO are permanent veto-holding members of the United Nations, Russia and China have spoke in concert over NATO strategies in the region and have called for a greater role for the SCO globally. Their similar political postures have manifested in their condemnation of the West’s strategy in the Middle East and their joint calls for the retraction of NATO forces in member states. In July 2005, for example, the forum demanded that the US and NATO “fix a date for their departure from military bases in Central Asia” which were originally set up as components of the military operations in Afghanistan in 2001. Though plans to withdrawal troops were originally repudiated, NATO pulled out its forces from the Karshi-Khanabad air base in southern Uzbekistan and Manas Base in the northern Kyrgyzstan.

The unanimity of Russia and China has also been displayed in areas of defence. The SCO has carried out several joint naval activities with its member states that have furthered concerns for the organization’s growing traction as a regional military coalition. A day after the summit culminated, China headed a series of military exercises in northern Tajikistan in an effort to promote multilateral counter-terrorism practices under an operational name Peace Mission 2012. While the SCO has eschewed from labeling such exercises as part of a larger strategy to become a military bloc, collective exercises of this nature can enhance the SCO’s strategic cohesion and serve to deepen its defence and security cooperation.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=” http://www.foreignpolicy.com/files/images/china_karzai.jpg ” captiontext=” Afghan President Hamid Karzai with Chinese President Hu Jintao “]

The bid for Afghanistan

Calls for the departure of NATO in the region and the Alliance’s recently confirmed plans to retract from Afghanistan by 2014, have coincided with the SCO’s strategic plan to include this Central Asian state in the organization. Hu Jintao has stated “We will continue to manage regional affairs by ourselves, guarding against shocks from turbulence outside the region, and will play a bigger role in Afghanistan’s peaceful reconstruction.”

Afghanistan’s entry raises questions of how the SCO plans to move forward in its ‘peaceful reconstruction’ of the country, and more importantly who will take the lead in this endeavor. According to Zhao Huasheng, Director of the Centre for Russia and Central Asia Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai, “China and Russia have no joint approach to Afghanistan.” He argues, “Cooperation is basically limited to a common political stance.” The lack of concord between the two Asia powers has allowed China to take action within the diplomatic framework of the SCO as a vehicle for its economic engagement within member states.

This war-torn country has a devastated economy, but is home to both hydrocarbon and rich minerals. Understandably, China is working towards building good relations to secure access to these resources. As a precursor to the 12th SCO Summit, China’s state-owned National Petroleum Corporation signed a deal for the development of oil blocks in the Amu Darya basin in December 2011, becoming the first foreign company to extract Afghanistan’s oil and natural gas reserves. In addition to the diplomatic tactic to absorb Afghanistan into the SCO, Chinese President Hu Jintao launched the summit by offering a $10 billion loan to support economic development and cooperation among SCO member states.

These developments have strengthened the appeal of the organization among countries that are seeking diplomatic insurance or emerging from years of conflict, as in the case of Afghanistan. Either way, the SCO continues to gain political influence and with China spearheading the organization’s initiative, the group continues to expand its agenda from mutual peace and security to development and reconstruction. This enlargement should be of great concern for NATO. As it wearily releases volatile states like Afghanistan, rising countries like China and its consortium will attempt to fill the gap, to gain access to resources and alliances that furnish political leverage. While these alterations in regional and international relationships could be favourable in the long term, the intermediate events that transpire signal a broader and more stringent shift in the balance of power between the East and the West.