The status of women in Pakistan is incredibly grim. The country is the third most dangerous in the world for women and girls and it is ranked 134 out of 135 countries on the World Economic Forum gender gap report, “due to a lack of economic opportunities, denial of access to education and health, and under-representation in politics and decision-making.” Women and girls are routinely raped and sexually assaulted, with little to no consequences for their attackers, and 90 percent of Pakistani women are victims of domestic violence. Most Pakistani women are forbidden to leave the house without their husbands’ permission, yet there is the unlikely paradox of these women being their families’ primary breadwinner. While women are subordinate to their husbands and fathers, many men are faced with the inability to find work, and thus tolerate their wives working because they can then collect the income. Cultural norms of female subservience are compounded by a justice system and a government that does not protect Pakistani women, partially due to a deeply ingrained patriarchal mentality and also as a result of Pakistan’s incomplete institutionalization. This legacy has produced a country whose state apparatus has failed to effectively penetrate society.

Pakistan is a notoriously weak state with an “incoherent, fragile [and] dysfunctional political system”. Its apparatus is fragmented and its central government struggles to exert control over the entirety of its territory. Pakistan is plagued by a multitude of special interest groups, including tribalists and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, who seek to advance their own vision of the country and who elude government efforts to bring them under state control. The Taliban arguably present the largest threat to the empowerment of Pakistani women, shutting down girls’ schools and creating a climate of terror after shooting 14-year-old girls’ education activist Malala Yousafzai.

Considering that the Taliban is virulently opposed to western influence in the region, attempts by foreigners to promote female development could give rise to increased attacks on girls and women. Malala Yousafzai’s case offers an example of this, with the Taliban justifying their attack because Yousafzai was “pro-west [and] promoting western culture in the Pashtun areas.”

Pakistani women remain subject to the norms of their religion, which largely keeps them in a subordinate role, particularly if they fear punishment from male family members. This is particularly true of women living in Pakistan’s extremely conservative Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), as tribalists present another obstacle to women’s empowerment in the country. Pakistan’s tribes have historically resisted cooptation by the state and tribal leader’s taboos, in addition to fear of Taliban retribution, significantly limited female voter turnout in the last election. Women often live in female-only areas of the home and are essentially prohibited from leaving the home for any reason. In such a restrictive community, few women would dare defy a ban by tribal elders, which effectively eliminated any chances of these Pakistani women taking to the polls.

There are undoubtedly issues surrounding foreign aid to women in Pakistan, particularly the ways that this aid might come into conflict with local customs and culture. There is also a robust debate regarding the provision of foreign aid more generally and the most effective means of targeting such funding. While these difficulties remain, there is little doubt that female empowerment is necessary and desirable both to the women in question and to the development of the Pakistani state. In a state so weak that it appears that government officials were unaware that Osama bin Laden was taking refuge on their soil, the expansion of the democratic process to all members of society is invaluable. Through bettering the status of women, the state could be strengthened, as it would lead to increased female participation in politics and thus the expansion of substantive democracy within the Pakistani population. A government that is more representative of its citizenry could eventually induce greater confidence in the democratic process. This last point is particularly crucial, as an overwhelming number of Pakistanis have little confidence in their government.

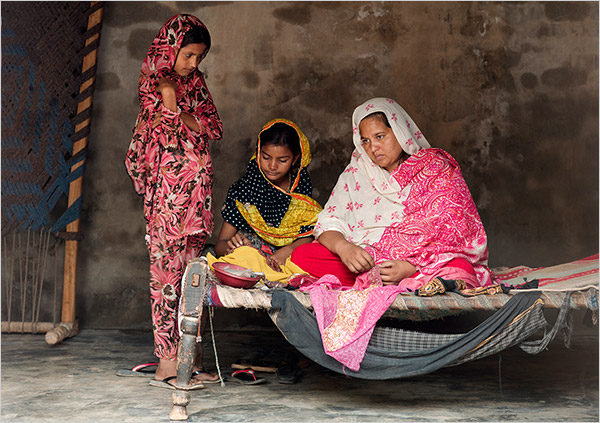

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/s300_greening.jpg” captiontext=”UK Development Secretary Justine Greening travelled to Pakistan in July 2013 to announce a new development program that targets women’s political participation among other things.”]

Change will initially be slow in terms of narrowing the gender gap in Pakistan as the majority of men are still opposed to women voting. Yet it is possible that through an increased presence of women in politics, Pakistani men might become more accepting of them in this role. Many men accepted women’s productive capacity as breadwinners only after seeing financial evidence of their abilities. Women in Pakistan also appear to be motivated to achieve their political goals. Many have defied their tribal elders by taking part in election training. As such, there is hope that they could also see value in women’s participation in political life, if these women continue to receive the support necessary to achieve their goals. The fact that women were able to run for election in both the FATA and other regions of Pakistan and win 16 seats also indicates a change in the national consciousness and increased acceptance of women in politics.

In order for Pakistani women to participate in politics and improve their lot in life they need to be endowed with the necessary skills to express themselves in the political arena. A UK development program is seeking to achieve this outcome. Following the success of a pilot project, the UK Development Secretary Justine Greening has announced that about one million Pakistani women will be supported by the program, which targets political participation, education, and healthcare. This program will make Pakistan the largest recipient of UK bilateral aid, under the condition that the Pakistani government also undertakes widespread reforms to improve tax collection and remedy corruption.

Efforts to improve female political participation in Pakistan are urgently needed. Due to inadequate registration of female voters, approximately 11 million Pakistani women were not able to vote in the most recent election. Despite this, it is important to note that 40 million women were registered to vote in this same election, a figure that has increased by 86 percent in the past three years and which demonstrates the determination of Pakistani women to have their voices heard. The problem with such figures, of course, is that voter turnout often does not mirror registration. The UK development program will attempt to harness this determination, educating local women on their rights, as well as advising them on how best to exert influence on different levels of government. On the flip side, government officials will undergo training on implementing laws that focus on female empowerment.

As Mohammed Hanif has stated, “an educated female population is more threatening to [the Taliban] than armies equipped with all-seeing drones.” A stronger, more democratic Pakistani state could serve as a bulwark against Taliban influence in the region and promote peace and security in the Middle East.