In July the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) announced the creation of a new $100 billion Development Bank (NDB). Ignored and underrepresented in Western-led development efforts, these emerging economies have used their newly realized weight in international relations to compete against the familiar World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Though lauded by those critical of U.S. dominated development banks, the underlying political objectives of the NDB are yet to be realized.

In July the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) announced the creation of a new $100 billion Development Bank (NDB). Ignored and underrepresented in Western-led development efforts, these emerging economies have used their newly realized weight in international relations to compete against the familiar World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Though lauded by those critical of U.S. dominated development banks, the underlying political objectives of the NDB are yet to be realized.

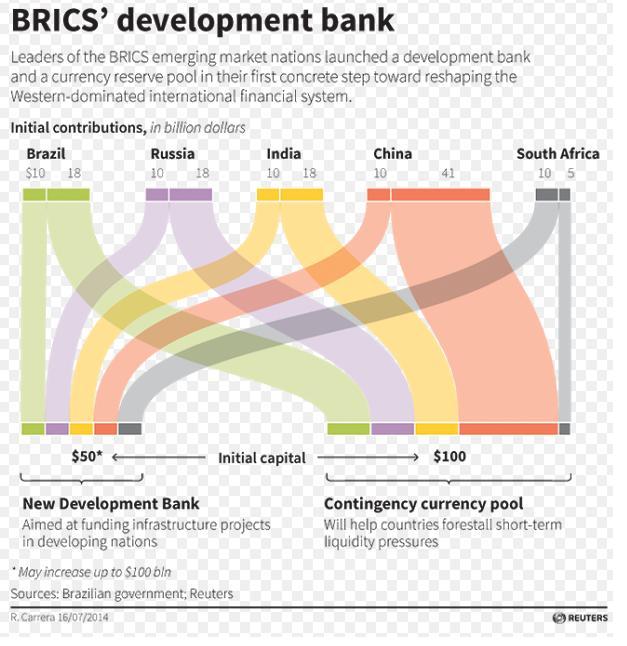

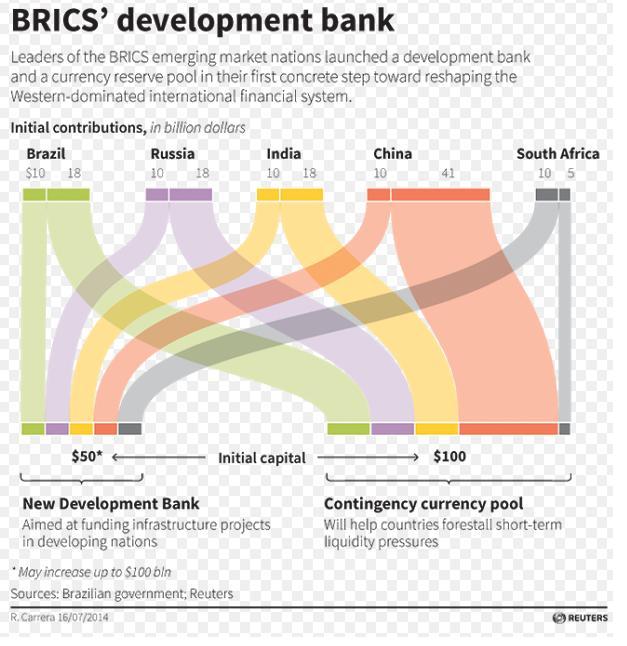

Looking to invest in long-term infrastructure and sustainable development, the NDB has gathered initial capital amounting from $10 billion – $50 billion from each member nation. The BRIC countries created a $100 billion Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) as a precautionary measure to balance of payment demands. However, the CRA has a 41% contribution from China, 18% from Brazil, India, and Russia, and 5% from South Africa, giving China the top shareholding position.

Those who condemn the conditions attached to IMF and World Bank loans and label these institutions an American foreign policy tool have celebrated the creation of a development bank outside the influence of the West. However, skeptics of these institutions have ignored the possibility of the NDB as the most politically and economically motivated actor yet.

Given a newly acquired taste for capitalism, China has created unsettling relationships with many corrupt regimes possessing an abundance of natural resources. Ultimately, while many would like to believe in an altruistic Chinese government, Beijing has had three major objectives concerning foreign aid. In particular, China has looked to secure oil supplies to feed growing domestic demand, position itself as a dominant player in the international energy industry, and create jobs for unemployed Chinese workers. Further, as the leading state and highest contributor to the NDB, the Communist Party of China may come to dominate institutional operations and funding priorities within the organization.

One may ask, as long as a country provides aid, does it matter what incentive they have to do so? And the answer is yes.

Although the IMF and World Bank have been accused of promoting American interests through inefficient and unethical practices, international watchdog organizations and the mass media have succeeded in suppressing these geopolitical calculations.

China, however, has remained ignorant of international norms and continues to pursue policies to the detriment of developing nations. Specifically, with economic and political objectives in mind, Beijing has supported repressive regimes and implemented myopic and narrow-minded development projects. The case of China in Angola exemplifies this point. Since 2006 Angola has been devastated by civil war and began searching for reconstruction funds. Offering loans to the government in Luanda, the IMF stipulated transparency measures to curb corruption and improve economic management. Finding these stipulations unattractive, Luanda accepted a less inhibiting counter-offer from China’s credit agency. Uninterested in internal affairs, China’s only stipulation was for Angola to supply a specific amount of crude oil per day, and award Chinese companies a certain amount of construction contracts. Consequently, by leveraging cash to ensure access to raw materials, employment opportunities and a new international alliance, the Chinese government undermined efforts by Western governments to reduce corruption and authoritarianism. Further, by requiring that infrastructure construction and other contracts favor Chinese service providers, Beijing is creating jobs for Chinese people in a sector that Angolans rely on for employment opportunities.

Though Beijing will not exclusively govern the NDB, China’s dominant position is bound to create coordination issues within the nascent organization. While the NDB’s projects will surely confer benefits to currently unaided recipient nations, one only has to look at China’s past development efforts to see that short term benefits of unstipulated aid may only serve to conceal the long term consequences associated with governmental corruption and autocracy. Thus, while we would all like to believe in a benevolent effort to develop the poorest nations in the world, the possibility of China gaining control over operations and funding priorities within the New Development Bank may be more dangerous than advantageous to the progress of developing nations. Christopher Abbott