The focus of Canada’s diplomacy in resolving the problems between Afghanistan and Pakistan needs to shift from its current emphasis on building trust to a mutual toleration and self-interests centered approach. These countries have a long history of the simultaneous processes of confrontation and mediation to settle their disputes. The Afghan government opposed Pakistan’s membership to the United Nations in 1947. However, diplomatic ties were later established between these neighbors despite the negative first impression. These countries went close to war twice in early 1960s, as a result of an interventionist foreign policy Afghanistan had in support of Pashtun and Baluch nationalists. In response, Pakistan provided support and safe havens for radical Islamic groups fighting the Afghan government. As a back house for Afghan Mujaheedin and later on the Taliban, Pakistan became a key determinant of Afghanistan’s political future.

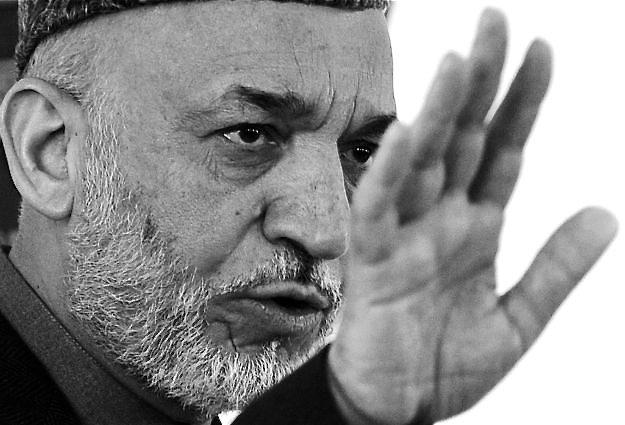

In early May of this year the situation between these neighbors escalated once again as they traded heavy-weapons fire over a border outpost, a checkpoint, and other installations recently built by Pakistani border police. These new facilities were constructed along the edge of Goshta district, which is located in Afghanistan’s eastern Nangarhar Province on the disputed border known as the Durand Line. England created the Durand Line in 1893, an arbitrary 1500-mile border between British India and Afghanistan. Although the line was planned initially as a buffer between Russia and the British Empire, it was made a permanent border in the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 without consulting the Afghan government. The people of Afghanistan have never accepted the Durand Line, despite its widespread international recognition. In reaction to the recent hostilities, Afghan President Hamid Karzai publicly accused Pakistan of destabilizing Afghanistan’s security and for the first time publicly stated that Afghanistan will never recognize the Durand Line. In response, Pakistan’s Foreign Office called the Durand Line a settled issue and accused Afghan officials of distracting from the more pressing issues requiring prioritized attention and cooperation. Regardless of what these neighbors do to each other or their statesmen say, fear and distrust have been persistent in the nature of their relations.

As US and other NATO troops begin to withdraw from Afghanistan by 2014, cooperation between Afghanistan and Pakistan becomes vital in fighting terrorism and maintaining international security. Committed to international peace and security, Canada has been promoting regional diplomacy initiatives through economic development and diplomatic support specifically addressing cross-border disputes. Canada continues to promote bilateral cooperation between Afghanistan and Pakistan in order to ensure lasting results for the progress that Canadians had made in Afghanistan. Initially known as the Dubai Process, the Afghanistan Pakistan Cooperation Process (APCP) forms the cornerstone of Canada’s foreign policy in Afghanistan. During their first joint workshop, held in 2007 in Dubai, key issues of counternarcotics, managing the movement of people, customs, and law enforcement were put in an action plan. At the beginning there was optimism about the process, however it wasn’t long lasting as little has been done to implement the agreed action plan.

Inherently, the Dubai Process heavily relied on building trust between parties apart from addressing the fundamental problems of border disputes, water management, and Indian presence in Afghanistan, which is considered a threat to the security of Pakistan. Focusing solely on building trust squandered Canadian resources and diplomatic effort put forth. In addition, the conflicting parties developed a sense of apathy toward the process making future negotiations hopeless. So what could be done to assuage the current state of hopelessness? Lester Pearson once said, “we must keep on trying to solve problems, one by one, stage by stage, if not on the basis of confidence and cooperation, at least on that of mutual toleration and self-interest.” Pearson’s words speak volumes here; Afghanistan and Pakistan are not at the stage in which they can cooperate on the basis of trust, but rather in recognition of their self-interest. Perhaps this way resources and diplomatic efforts would not be exhausted and relations between these neighbors could move toward a meaningful cooperation.