Barriers to Reform

Despite being in crucial need of reform, the likelihood of any substantial changes being made to the Security Council is low. This is primarily due Articles 108 and 109 of the Charter of the United Nations, which state that any amendments or alterations to the Charter must be approved by a two-thirds majority vote in the General Assembly and, more importantly, by all the permanent members of the Security Council. Thus, the UNSC faces the same problem with passing reforms as it does with passing resolutions: the need to get everyone’s approval hampers the Council’s ability to implement effective and necessary reforms. It is well within each of the P5 member’s national interests to keep their veto power and ensure their geopolitical adversaries do not accede to the UNSC, which ultimately means that any proposal aimed at revoking the veto power or expanding membership to the G4 faces an uphill battle.

Vetoing Veto Reform

Though democratizing the Council would be an ideal change, the reality is that the veto-wielding members of the P5 would not altogether vote to limit their own power. Paradoxically, a proposal to remove the veto power would likely be vetoed itself by one of the P5. For France and the UK, both of whose influence has waned since the Council was established in 1946, the veto increases their power and capabilities within the international community. Hence, it wouldn’t make much sense for these states to vote to remove that power without significant concessions and assurances in return.

Similarly, despite Putin’s recent meddling in Eastern Ukraine, Russia’s influence has also decreased dramatically since the end of the Cold War. The state’s ability to pursue its interests is challenged by numerous demographic problems, including widespread substandard health conditions and a population in sharp decline. To compensate for its dwindling global clout, Russia has frequently used its veto to assert its influence, employing it eleven times since the fall of the Soviet Union. Consequently, eliminating the veto would result in a further degradation of Russia’s influence, so clearly any proposal aimed at doing so would face strong Russian resistance.

New World, Old Enemies

Permanent membership expansion also faces a host of challenges. Rivalries between some prospective permanent members and states already in the P5 will stymie the process of expansion, as P5 members could use their veto to block the appointment of any new candidates. China’s longstanding rivalry with Japan, which has been further exacerbated recently over territorial disputes, would likely result in China’s vetoing of any plan to extend permanent membership to Japan. After the US endorsed Japan as a candidate for permanent membership in 2005, riots broke out in Beijing and the Chinese government strongly opposed the move. Consequently, China’s strong opposition to Japan negates the possibility of all the G4 members assuming a permanent seat together. Beijing even indicated it would support India’s bid, at the risk of harming its relationship with Pakistan, as long as India did not pursue membership cooperatively with Japan.

Most of the P5 states independently support the aspirations of the G4, but because the process of reform is so arduous and generally seen as improbable, leaders often provide rhetorical support that, politically-speaking, is high yield and low cost. President Obama, addressing the Indian parliament in 2010, endorsed India’s bid for permanent membership, but stopped short of offering a timeframe or concrete plan of action. Similarly, other P5 states have advocated for expanded membership and have endorsed the G4 states, but while their support is welcomed and lauded by aspiring permanent members, little action has been taken. In essence, the P5 members are able to score political points with the G4 states by offering their support for reform, but don’t actually expect any change to occur.

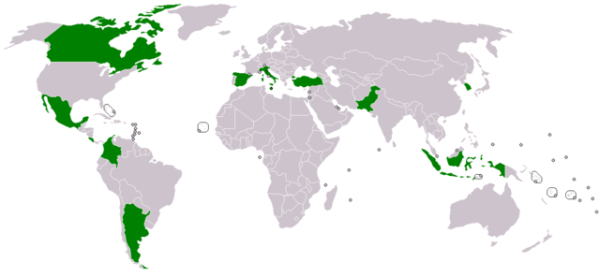

Lastly, even if the P5 miraculously supported the addition of new, veto-wielding permanent members, the decision does not lie entirely with the Security Council. Rather, there are rivals of the G4 in the General Assembly who might vote against bringing Japan, Brazil, Germany, and India into the Security Council. To counteract the G4, the Uniting for Consensus (UfC) coalition formed to oppose the G4’s proposal of increasing the number of permanent members, and instead advocate for increasing the number of non-permanent seats from 10 to 20, while keeping the current P5 structure. Led by Italy, the UfC includes Canada, Argentina, Spain, Mexico, South Korea, Pakistan, and Turkey, as well as a collection of smaller states. The group as a whole opposes adding any new permanent members, however some members of the UfC are regional rivals of various G4 states and have a direct interest in keeping them from gaining permanent status: Italy would rather see a common European seat as opposed to one occupied by Germany; Mexico and Argentina oppose Brazil’s candidacy; India’s bid is strongly rejected by Pakistan; and South Korea opposes Japan’s membership. These UfC rivals are influential in their own right and play a notable role in both maintaining the global economy and funding UN operations. If the UfC coalition can sway other members of the General Assembly – or even non-permanent members currently occupying a spot of the Security Council – into voting against expanding permanent membership, it is unlikely that any meaningful reforms could be instituted.

The Future of the Security Council

Though clearly in need of a serious makeover, the Security Council faces barriers to reform that are essentially insurmountable. Some states have put forward modest proposals for reform, such as the UfC’s suggestion of adding more non-permanent members, or adding new permanent members but not granting them a veto power, yet these changes would not improve the efficiency, effectiveness, or legitimacy of the Security Council. Unfortunately, the current climate suggests that the Security Council will likely fail to enact any meaningful reforms in the near future, and as a result, the international community should refrain from looking to the UNSC for an answer to the world’s more severe – and seemingly more frequent – conflicts.