A Broken System

The international community is currently overburdened by a variety of conflicts. And as the institution tasked with international conflict management, the UN Security Council (UNSC) is juggling the crises in Gaza, Ukraine, and Iraq, trying to at least mollify the tensions between warring parties in hopes of attaining some stability. However, the Security Council has not sanctioned any meaningful intervention in these conflicts, nor has its actions in Syria been able to end the country’s three-year long civil war, which has thus far claimed over 150,000 lives. The failure of the UNSC to manage these crises is due primarily to institutional flaws that make it nearly impossible for the Council to sanction a strong international intervention. Most prevalent of these flaws are the unreasonable powers afforded to the UNSC’s permanent members and the out-dated structure of the Council.

The Veto

One power that impedes the UNSC’s ability to effectively manage international crises is the veto power wielded by the Council’s Permanent Five (P5) members: Russia, China, the US, the UK, and France. For a resolution to be passed in the UNSC, the P5 have to unanimously agree on – or abstain from voting on – the resolution, and thus any proposal can be thrown out if one party chooses to vote against it. Ultimately, because the P5 countries vary greatly in terms of their political, economic, and security situation, consensus is hard to form on a number of important issues due to the inevitability of a divergence in interests. Even if a resolution is passed, the need for consensus ensures the result will be a weak and highly diluted statement with little force or effect.

Recent uses of the veto include the United States’ rejection of resolutions concerning increased political status for Palestine, Russia’s rejection of a resolution regarding the crisis in Ukraine, and Russia and China rejecting multiple resolutions attempting to address the Syrian civil war. All of these proposals concerned issues of considerable international importance and had the agreement of the majority of the P5, however they were rejected due to the objections of only one or two parties. As former French ambassador to the UN Gérard Araud notes, a P5 nation will block intervention by the Security Council in any conflict where its national interests are involved. Consequently, Arnaud asserts that the UN is only “in charge of crises that are of no interest to anybody.”

Representation in the Council

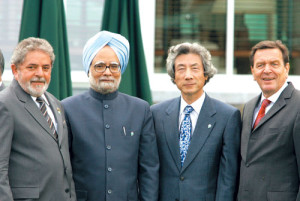

Apart from the woes brought on by the veto power, the structure of the council is out-dated and poorly reflects the geopolitical realities of the modern world. Rising powers such as India and Brazil, entrenched economic powers such as Japan and Germany, regional powers such as Nigeria and South Africa, and regional organizations such as the European Union and African Union, have all grown to become significant players in the international system, and these actors assert that they have a legitimate claim to a permanent seat on the UNSC.

Brazil, India, Germany, and Japan, who collectively make up a group known as the G4, support each other’s bid for permanent membership and are among the most vocal lobbyers for expanding the UNSC. The G4 nations play a considerably more important role in the world today than they did at the time the UNSC was formed, nearly 70 years ago. India, Japan, Germany, and Brazil now have the fourth, fifth, sixth, and eighth highest GDP respectively, account for nearly one quarter of the global population, and collectively spend over $175 billion annually on military expenditures. Furthermore, the G4 contribute significantly to the operating budget of the UN. Germany and Japan together provide almost 20% of the UN’s peacekeeping funds, while India is the third highest contributor of peacekeeping troops. Considering their increased role in the UN and the international system as a whole, the G4 strongly insist that they should be included as permanent members of the UNSC.

Reshaping the Council

For the UNSC to retain its legitimacy and improve its effectiveness, reform is a necessary step. To become more representative, the UNSC should expand its permanent membership from five to nine by including the G4 nations. This move would create a body that acknowledges the current distribution of power and influence in the world: the P5 and G4 nations have a combined GDP of roughly $46 trillion, accounting for over 60% of the global GDP, and comprise nearly half of the world’s population. The new P9 would also constitute nearly 60% of the UN’s budget contributions and provide almost 15% of its peacekeeping personnel. Taking all of this into account, clearly a Security Council that includes Germany, India, Japan, and Brazil would better represent the distribution of global power and importance, thus it is logical that these nations should be afforded a seat at the high table.

Critics of reform often argue that the effectiveness of the UNSC would suffer if membership were expanded, as unanimous agreement on resolutions would be less likely. The result would be a council that is even less effective than it currently is. In order to improve both representation and effectiveness, the veto power should be disregarded altogether, and instead resolutions should be put to a vote where a majority is needed to pass a resolution rather than unanimity. This would not only increase the number of resolutions the council is able to pass but would also make those passed stronger, as there would be less of a need to water down the language in order to garner universal support.

Including the G4 as permanent members and eliminating the veto power would be ideal reforms for bolstering the effectiveness and legitimacy of the UNSC. But to ensure that the Council continues to have a hand in international conflict management, the UNSC should be malleable and capable of reforming to meet the demands of a changing international system. Future reforms might include combining the seats held by the UK and France into a single European Union seat to better represent the continent’s interests. Similarly, the UNSC should at some point consider extending membership to regional powers in Africa. Despite being the second biggest continent and having a rapidly expanding population, which currently sits at over 1.1 billion people, there is no permanent seat reserved for Africa. The G4 supports the addition of a permanent African seat, indicating that if the G4 were to meld with the P5, the African Union, Nigeria, or South Africa might be candidates for the next round of membership reforms.