Any hope for ending the Syrian civil war is subsiding. Since the inception of the conflict the international community executed plans for the imposition of ceasefires and, sadly, all efforts failed.

The first strategy was conducted by the Arab League in November 2011. Violence between state and non-state actors had been going on for seven months at the time. Some noteworthy points focused on open dialogue between the warring parties and halting all violence. Unfortunately, it failed because the Syrian regime did not bind itself to the plan. Rather, it continued to carry out violent attacks against Syrians.

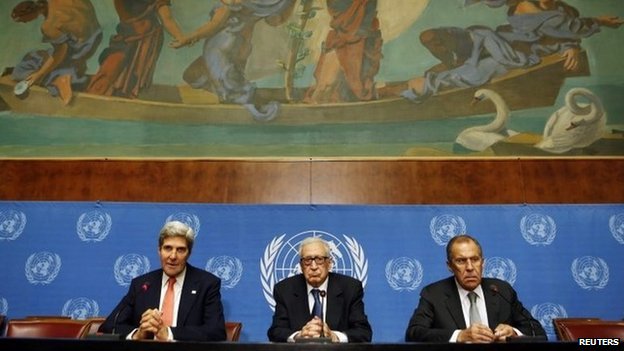

Another plan was executed by Kofi Annan, former Secretary General of the UN. The six point peace plan included a ceasefire that would assist with the termination of armed violence, and broker a daily pause for humanitarian reasons. Both parties failed to respect the ceasefire, and violence between the warring parties did not stop. Each warring party’s unwillingness to find a solution for de-escalating the violence is a consistent pattern that continues to this very day. For now, the second round of the Geneva II peace talks might result in small concessions rather than an overall deal that will end the conflict. This comes as no surprise since the relationship between both parties is based on mistrust.

Understanding the Syrian Conflict

Syria is in in a state of civil war but it also envelops a microcosm of other conflicts. During the Syrian uprising, the state experienced a value-based conflict that revolved around reforms. At this time, the overall goal of the protesters was to transform Syria’s government into a more appropriate and equal system that would ultimately improve the lives of civilians.

It also became a data conflict because the root cause for the protests has been misconstrued; “terrorists” have been depicted as the root cause for Syria’s turmoil. Labeling civilians as terrorists is extremely important because it is also a determinant for mass defections. For example, Syrian regime commanders managed to maintain a façade that labeled ordinary civilians as terrorists, thus justifying the use of violence against innocent people and this is what ultimately led to defections. Rather than implementing meaningful reforms for the betterment of the Syrian people, violence was continually used as a tool for controlling the situation.

Next, it is a relationship conflict because there is a continuity in negative behaviour between actors and miscommunication is prevalent. Mr. Assad has stated that he will not negotiate with “traitors.” It is important to note that the Syrian opposition is depicted as a traitor and as foreign backed “terrorists.”

Finally, it is an interest conflict because neither Party will step down. For the Syrian opposition, the ultimate goal, as stated in the Geneva communiqué, is to establish a transitional government, whereas the Syrian government has firmly stated that Mr. Assad’s resignation is not up for debate. The conflict is embedded in issues that cannot be easily solved and any form of reconciliation between all key players is currently unattainable.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/89065372-2C6A-407F-B8F2-E1A43B881ABF_mw1024_n_s.jpg” captiontext=”Syrian opposition chief negotiator Hadi al-Bahra and General Secretary of the Syrian National Council Badr Jamous arrive with the opposition delegation”]

The Deadlock Continues

Anas Al Abdeh, a senior member of the Syrian National Coalition, stressed the opposition’s stance on Syria’s future, which is “to work on establishing a transitional government body with full executive authority and power over all state institutions, including army and security forces with the consent of both parties.” Unfortunately, mutual consent for a transitional government is not attainable. Determining if Mr. Assad will continue to hold Syria hostage or if the opposition’s call for a transitional government will be heard is solely dependent on the international community and its willingness to intervene militarily.

The opposition and Syrian regime are divided over the aims of the peace talks. As one party insists on the removal of Mr. Assad, the other wants to find a solution for removing the foreign-backed “terrorist” groups fighting in Syria. As the peace talks come to an end, UN mediator for the Geneva II peace talks, Lakhdar Brahimi, summarizes the experience by stating that little progress has been made. To no surprise, the political deadlock will remain.

The second round of peace talks are expected to continue on February 10. The contentious issue of a transitional government will continue to be discussed in the near future but the possibility of the Syrian regime agreeing to establish a transitional government is unlikely. Since the onset of the conflict, the regime carried out an aggressive and violent campaign against its own people and it will continue to do so. A regime that deliberately demolishes rebel-held neighbourhoods and targets communities that are accused of supporting the opposition is not employing a legitimate tactic of war. We must question why the regime would agree to form a transitional government when it has carried out numerous war crimes for the purpose of maintaining control.

Lakhdar Brahimi warned us in November 2012 about the possibility of Syria becoming the new Somalia, where there was no functional government and fighting between warlords and militias is present. Various factions in Syria are competing for power and the difficult truth is that Syria could undergo a similar fate.