On 11 June 2020, Dr. Robert M. Cutler, Director of the Energy Security Program, spoke to a webinar “Energy Issues in the Post-Covid World”, organized by the Center for Analysis of International Relations, Baku, Azerbaijan. This is a transcript of his remarks.

I have been asked to discuss energy issues in Eurasia. The easiest way to do this is geographically, starting with Beijing and, as it were, working my way west to Brussels. Concerning China, the question is the nature of its relations with Russia and Central Asia, and the role of energy in these relations.

Already these relations were problematic before the economic shock resulting from the lock-down that governments enforced following the appearance of the virus. Chinese-Russian relations have not reached the level of strategic cooperation for which Beijing had hoped with the treaty in 2001. Military cooperation has reached its limits, and Russia is all too aware that it is turning into a mere raw-materials supplier to a wealthier and more technologically advanced China.

The power of Siberia two project has already developed problems. China’s demand for imported natural gas has decreased due to its economic decline and increased imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Turkmenistan especially has been feeling the effects. The statistic is sometimes cited that renewable energy comprises slightly over a quarter of total Chinese power generation, but the vast majority of this is from hydroelectric sources.

China’s capacity for investment as well as production in non-hydroelectric (excluding nuclear) renewables will decline as its economic decline deepens and foreign direct investment flees for other lands as international companies reconfigure their global supply chains and as calls for sanctions due to human rights violations (not just in Hong Kong but also in Xinjiang not to mention Tibet) gain greater traction. Both these trends were under way for two to three years before the present situation.

China’s exit from the crisis, and indeed the whole of Eurasia’s exit, will be conditioned by the fact that the situation has demonstrated that the role of the United States. Dollar as the global reserve currency is unchallengeable. It will remain so for at least the rest of our lives. The economic and financial consequences of the lock-down demonstrate that cryptocurrencies, gold, the euro, the yuan: none of these is available in sufficient quantity or has sufficient worldwide confidence to play a reserve-currency role.

These circumstances are important because the structure of the global macro-economy necessarily constrains the possibilities for the development and exploitation of energy resources, whatever their type. Sovereign defaults and unilaterally declared debt moratoria have already started to take hold worldwide.

India has at least the opportunity to come out of the crisis in relatively better shape than much of the rest of Asia. That is because some global supply chance fleeing from China are setting up in India even despite known infrastructure problems. Moreover, the national demographics of India foresee continued growth of the working-age population for decades to come, in contrast for example to China.

Geo-strategically it is projected that India will emerge with the world’s third largest navy by the early 2030s, also boasting aircraft carriers that will surely patrol the Indian ocean. Aside from a relative lack of domestic infrastructure, India’s main problem is the choke-hold that its electricity boards have on electricity production and distribution and the associated instability of supply for industrial purposes. At the consumer level, it is certainly possible that renewables will help to lift the quality of life of the rural population.

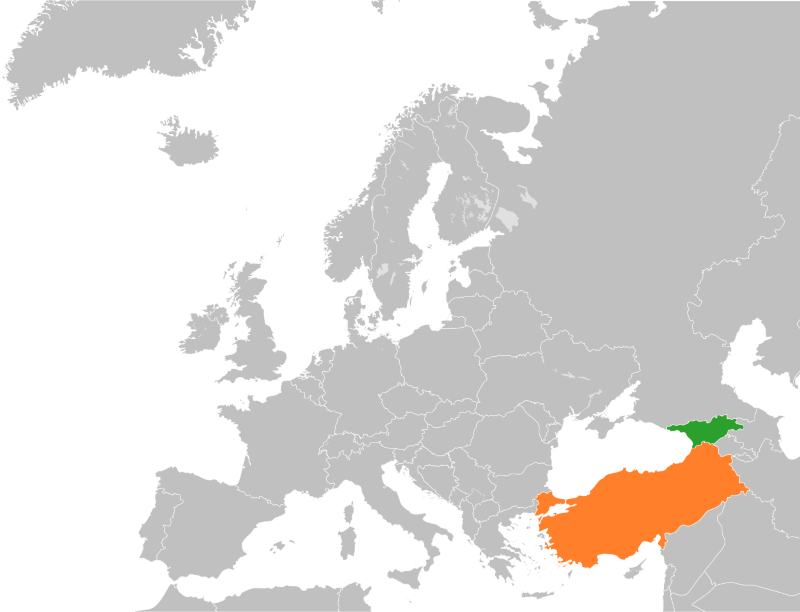

The Indian rupee has been surviving the crisis in much better condition than the Turkish lira. The energy situation in Turkey is extremely complex and not easily summarized, but it is clear that natural gas from the Caspian Sea region is destined to play a greater role there.

Let me now jump to discuss some of the concerns of the European Union and Brussels, before moving back east from there to finish my remarks speaking about the South Caucasus.

The EU is set to use pandemic recovery funds to boost production of green hydrogen (from renewable energy) as well as blue hydrogen (from natural gas). However, the cost of producing green hydrogen is still appreciably higher than for blue hydrogen. Although the EU’s objective is a full transition to green hydrogen, natural gas and blue hydrogen will still be required for many years to make the eventual green transition less expensive.

The coronavirus pandemic makes Central Asian gas exports to the EU even more timely, because these would make its energy transition less expensive. At a time when many other infrastructure projects requiring greater upstream investment are being cancelled or delayed, the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP) is again appearing on the international political and economic agenda. The current extremely low prices for natural gas make the TCGP’s construction very affordable, and no upstream investment is required.

Although the pandemic will decrease energy investment in general worldwide, the EU situation is expected to be different, because the EU has decided to apply a significant part of the recovery funds precisely towards the energy transition. The pandemic thus enhances the timely advantages of sending Central Asian gas to Europe.

Gas from Turkmenistan costs much less than gas from Siberia. As European hydrogen demand develops, carbon captured from Turkmenistan’s natural gas can be easily stored in Azerbaijan’s depleted hydrocarbon deposits. Azerbaijan could use Turkmenistan’s gas to feed its own burgeoning petrochemical sector.

Turkmenistan would welcome the chance to export to Europe. but only through a shore-to-shore pipeline connecting its integrated onshore pipeline system, including the shut-in wells in the east of the country, to Azerbaijan’s onshore system.

Additionally, Turkmenistan’s gas is paradoxically the closest to Europe. Only 300 kilometres separate Turkmenistan’s coast from the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP) giving access to TANAP and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline.

The TCGP would also be the signal for other trans-Caspian energy projects to go forward, just as in the 1990s the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil export pipeline was such a signal for the South Caucasus andAnatolia. Beyond Turkmenistan, benefits would extend to other Central Asian countries. Plans are on the drawing-boards for Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to join Turkmenistan in subsequent trans-Caspian energy projects. These would enable countries in the region to secure greater revenues independent of Russia and China.

Turkmenistan’s gas is the most economical for Europe. Gas from Central Asia is less expensive than from other sources, and fully independent of LNG prices. If Turkmenistan’s enormous gas export potential is not realized in a European direction, then it would be in Russia’s interest to purchase that Turkmen gas instead and to re-export it to the market in China. This would be less expensive for Russia than developing its own West Siberian resources for Chinese consumption.

Indeed, Gazprom has already been instructed to develop a pipeline system allowing such deliveries. Such a development would diminish the autonomy not only of Turkmenistan, but also of most other countries in Central Asia and the South Caucasus. Because of its strategic significance and its potential to catalyze further economic growth and reform in the Caspian littoral states, the TCGP may be the most important project for the region at the present time.

Photo: European Union, (2012). by Vladimir Simicek via EC – Audiovisual Service.