Hopes of finding a diplomatic solution to the Iranian nuclear program have soared in recent weeks. The election of the reformist President Hassan Rouhani is believed to represent a clear break from the antics of the Ahmadinejad era. And while many have questioned Rouhani’s sincerity, his recent phone call with President Obama, which broke a 34-year silence between the two countries at the highest level, should not be brushed off as insignificant.

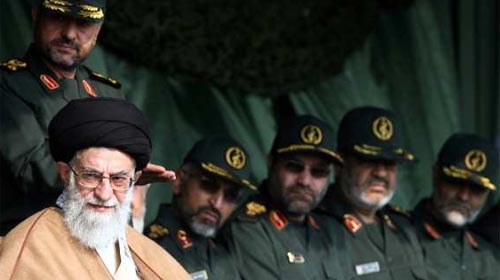

Yet for all of the optimism that Rouhani has cultivated in recent weeks, doubts remains over his ability to deliver change. Many commentators have pointed to the presiding influence that the Ayatollah Khamenei still holds in nearly all political matters, but few have addressed the importance of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the hardliners who make up its highest ranks.

Upon Rouhani’s return to Iran, the IRGC’s top commander, Mohammad Ali Jafari, wasted little time in criticizing Rouhani’s phone call with Obama as premature. Weeks earlier, the deputy chief of the Revolutionary Guards, Hossein Salami, contradicted Ayatollah Khamenei’s endorsement of “heroic flexibility” in negotiations, by announcing that the IRGC will show no flexibility when dealing with enemies of the political system. In fact, Iran’s hawks are increasingly lining up to express their doubts over the warming of US-Iran relations. Brigadier General Masoud Jazaeri of the IRGC recently communicated his own distrust of this current thawing, “Those who rest their hopes on the United States either do not know the US and the White House, or do not know politics.” But the IRGC cannot be ignored if a lasting diplomatic solution is to be brokered. In the long run, the IRGC stands to benefit significantly from peace and cessation of the sanctions against Iran.

Guardians of the Revolution

The IRGC was itself a product of the Iranian Revolution. Formed by the Ayatollah Khomeini, the IRGC was intended to serve as a rival army to safeguard the new regime from the threat of a military coup. But it was the devastating, 1980-89 Iran-Iraq War which forged the Revolutionary Guard’s identity as selfless defenders and war heroes of the Islamic Republic. Once the war ended, the IRGC redirected its forces to the task of rebuilding the war-torn country, and in the process the organization developed a financial empire which stretched across most sectors of the Iranian economy. Today, the economic clout of the IRGC continues to expand rapidly with many of the government’s major oil, gas, and construction contracts being awarded directly to the Guard’s engineering wing, Khatam Al-Anbia, or to firms owned by high-ranking members of the IRGC. The wealth accrued by the Guards has brought it considerable political sway. In 2009, the IRGC’s suppression of the Green movement activists was vital to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s electoral success. In the same year, the IRGC made a $8 billion investment in Iran’s telecommunications monopoly; a move that is widely seen to be a further flexing of the Guards’ political influence.

Engaging the IRGC

The IRGC cooperates closely with Ayatollah Khamenei and reporting directly to Iran’s supreme leader, which allows the Guards to operate without parliamentary oversight. Moreover, the political isolation that Iran endures has actually come as a blessing to the IRGC, whose economic activities have been shielded from international competition. Increasingly, the Guards’ attempts to obstruct fledgling US-Iran relations come less from ideology and more from financial pragmatism. But the IRGC has not been immune to the international sanctions placed on Iran, and the nation’s restricted ability to export oil has distressed the overall economic system. In the long term, the IRGC would stand to gain much from a liberalization of sanctions, and greater access to international markets.

To convey the merits of a diplomatic solution to the IRGC’s leadership, fears of international competition and change to the status quo must be assuaged. The IRGC can no longer be left on the sidelines. The international community must find a meaningful way to enfranchise and reassure this influential and wide-reaching organization in any future negotiations.