In the summer of 2009, amongst the busy schedule of blockbuster films by well-known directors, a relatively unknown South African director, Niall Blomkarp, released District 9. Despite a lower budget compared to its competitors, the film was a major success, and went on to receive critical acclaim for both its effects and its underlying commentary.

You might be asking yourself “what does District 9 have to do with international relations?” The truth is that the message put forth by Blomkarp about the issue of discrimination and inhumanity that is propagated by ignorance and populism relates greatly to contemporary global issues. From the governmental and corporate level to the communal level, District 9 prompts an ugly realization of how racism and fear can still permeate human relations.

The film sets the tone quite early, infusing a gritty realism to the setting through a series of documentary style interviews and amateur footage that provides viewers with the backstory. This will come to mirror the grittiness of the film’s content.

In 1982, an alien ship arrives over Johannesburg, South Africa, and hovers above the city for 3 months. Determined to make contact with the ship, a team of human experts force their way into the ship, only to discover a dying and impoverished species. Rather than dangerous and hostile, the aliens are shown to be vulnerable and aimless.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”200″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/finalpic.jpg” captiontext=””]

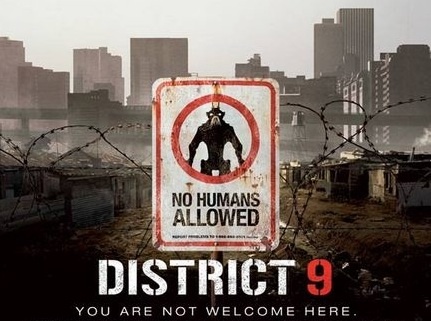

After this discovery, the aliens are relocated to a government camp beneath the ship, which is designated “District 9.” Due to the overriding military presence and general avoidance by its human neighbours, the camp quickly becomes dirty and disorganized, continuing the cycle of poverty that had existed before. The residents of Johannesburg are shown to be virulently anti-alien, with numerous signs in public spaces that read “no non-human loitering,” and a variety of street interviews with residents who are indignant that they are forced to share their city with such beings. What is more, the alien’s given scientific name is not deeply established, so they are derogatorily referred to as “prawns.”

There is, in essence, an overriding feeling of distance, in both physical and cultural terms, between the aliens and humans. In the wake of alien weapons caches being discovered, the concerns of many people indicate a rising tension between the two groups. Riots come to overtake the city, and the decision is made to evict the non-humans, violently or otherwise, and place them in new townships outside the city. As alien unrest increases in retaliation, the locals demand the immediate removal of all non-humans. In response to public pressure, the government hands over the relocation operation to a private company known as Multi-National United (MNU). In reality, MNU had a stake in removing the aliens in order to promote weapons research, while the government used the aliens as scapegoats for their own failed governance.

The film focuses on how tension between humans and aliens intensifies over the span of about 20-some years. It accurately depicts the “us and them” dichotomy that has prevailed throughout history by elucidating the way that distinct groups, often marked by racial differences, treat each other. Ultimately, discrimination towards the “other” leads to negative conflict and the film does its best to highlight this.

It is easy to see the parallels between the course of events in District 9 and the breakdown of human relations in the real world. What is notable is not the depiction of segregation and discrimination, but the cycle of fear, ignorance, and misunderstanding between the two groups that takes place over the course of the film and escalates to violence and hatred. Once the main character finds himself in need of an alien’s help, the prawns are shown to possess a humanity that is not skewed or merely reminiscent of our own, but identical to it. The xenophobia that the humans and aliens feel towards one another is misguided, with the current situation having come about by the meddling of the more radical and insidious actors, like the MNU and Nigerian gangs, seeking to take advantage of these feelings for their own gain.

The grotesqueness of the prawn’s appearance accentuates this message, contrasting the startling and foreign outward appearance of their bodies with the underlying humanness within. Over the course of the film the viewer is shown that the prawns simply seek the same right to live peacefully and without discomfort the way we do. Outward appearance, be it physical, cultural, or otherwise, means little when examining the common thread of humanity that runs through all of us.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/D6.jpg” captiontext=””]

Recalling District 6 and Forcible Displacement

It is no secret that the aliens from District 9 resemble the black African inhabitants who lived in the Cape Town area of District 6 during the Apartheid era. In 1966, the apartheid regime declared District 6 as an area for whites only. Consequently, coloured people were deemed illegal residents. Over the course of the next few years, the apartheid regime destroyed thousands of homes and forced coloured inhabitants to leave District 6. They were relocated to slum areas, also known as the city’s “dumping grounds.”

District 9 could also relate to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Israel’s policy of forcibly displacing a particular group, the Palestinian Arabs, and relocating them to designated territories is a clear parallel to District 9’s governmental actions. As an example, Israel’s Prawer Plan will destroy Arab Bedouin villages and forcefully relocate 70,000 people. Also, the plan deems the presence of this particular group illegal. Indeed, the Bedouin community has been the subject of discrimination for decades.

District 6 and the Prawer Plan are both racially-motivated projects and the film accurately depicts inhumanness in all its forms. Power over the “others” allows governments, multinational corporations, and communities to determine the fate of specific groups. District 9 showcases how human rationalization of mistreating others is often determined by differences that are ultimately meaningless in the larger scheme of common humanity.

What made the black Africans in District 6 so different from their white counterparts that they were so undesirable that they had to be forcibly removed? What was it about the Palestinians that brought the Israelis to force them out of certain areas? Indeed, what was it, really, that motivated the humans in District 9 to relocate the aliens? They looked different, they acted different, and they were difficult to communicate with.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/68148387_apartheid-whites-only-sign_getty_2659675.jpg” captiontext=””]

This is of course a simple message that brushes over many more complicated issues such as the deep historical grievances between blacks and whites in South Africa and the Arabs and Israelis in the Middle East, but it still rings true in the end.