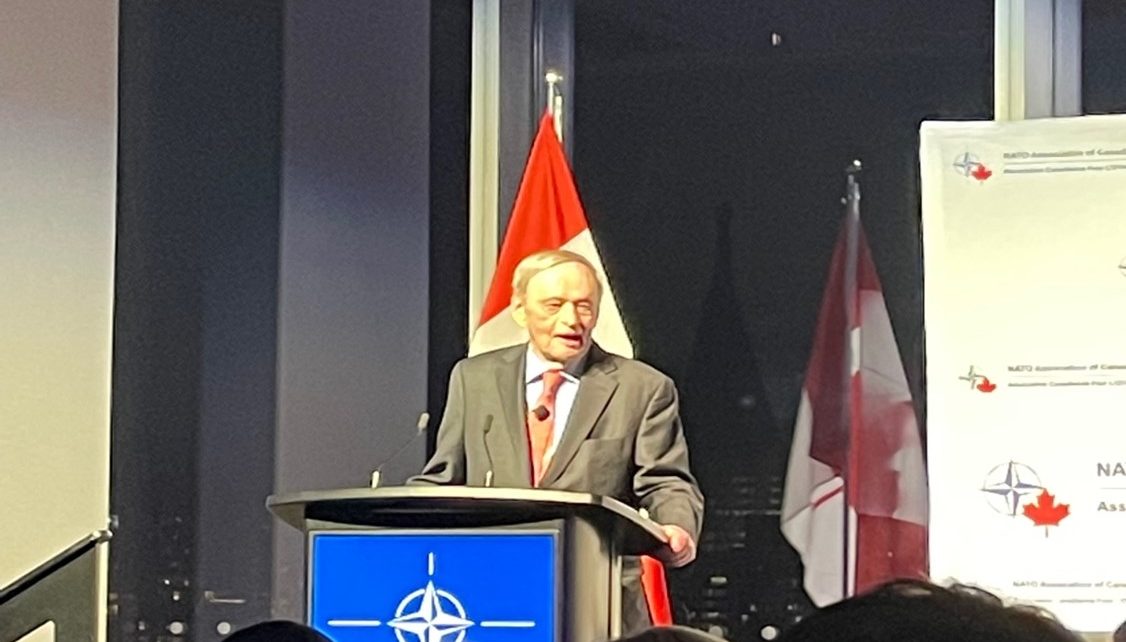

Jean Chrétien, Canada’s twentieth prime minister, had his audience in an effervescent mood on March 15th at the Globe and Mail Centre. As the guest of honour at an event organized by the NATO Association of Canada to recognize Mr. Chrétien’s legacy in Canadian foreign affairs and his contributions to the evolution of NATO, he was bestowed with the Louis St. Laurent Award. Exuding conviviality and sprinkling his remarks with well-timed wit, the eighty-eight-year-old retired parliamentarian put to rest any doubt that he can still work a room.

Notwithstanding the celebratory reason for the evening, a pall was cast over the occasion by the shadow of Russia’s unprovoked military aggression against Ukraine. After receiving his award, Mr. Chrétien assumed the lectern and commenced his remarks by intoning that Russian President Vladimir Putin would live to regret his country’s invasion of its neighbour for “many years to come” – a prophecy resonating with the accrued wisdom and credence of an elder statesman’s long life and breadth of perspective.

Mr. Chrétien appreciated the obvious serendipity of receiving honour and recognition from the NATO Association of Canada at the very moment when the importance of the mother organization it represents is more prominent in the Canadian psyche than it has been in a generation. The NATO Association’s peacetime endeavours to alert the Canadian public to the – at times, seemingly abstract – threats posed to the rules-based international order, and thus their way of life, is vindicated by the incarnation of those dangers in a real-world scenario.

Canada’s twentieth prime minister drew from his extensive personal experience in working with NATO at the highest diplomatic levels and presented the unvarnished truth about the alliance as an indispensable yet imperfect institution of multiple moving parts, with all the attendant complications that entails. In many ways, NATO is the offspring of the democratic way of life it was conceived to safeguard; it is an organization based on compromise, consensus, and the accommodation of competing viewpoints, not of dictatorial edict. With this operating system comes a bureaucratic slowness that at times frustrates even NATO’s greatest admirers, a sentiment that might resonate with anxious observers of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

Mr. Chrétien relayed a particularly arresting anecdote from January 1994, during the Balkan Wars, in which he recounted having to stand down some of his fellow NATO heads of state and government who were intent on bombing Serb forces in Srebrenica. Since Canadian peacekeepers had been committed to that theatre, they would be vulnerable to such an operation. “You’re willing to fight until the last Canadian,” he recalled saying to another Allied leader.

As the former prime minister stepped back from the podium and sat to join Nathalie Des Rosiers, Principal of Massey College, for the informal ‘fireside chat’ segment of the evening, the extent of his political pedigree was on full display as he recalled events from his career that now lay sixty years in the past. He described the work of Prime Ministers Louis St. Laurent and Lester B. Pearson, who he counted among the architects of NATO in its embryonic phase. Mr. Chrétien spoke, not with the scholarly detachment of one who only knows their work from the historical record, but as one who knew both men personally. Prime Minister Pearson, Mr. Chrétien reminded the audience, recruited him as his parliamentary secretary at the young age of thirty. These were men of peace, he emphasized, but they were not naïve.

Mr. Chrétien edified the audience by situating Mr. Laurent’s and Mr. Pearson’s approving attitudes toward NATO in the broader narrative of their well-known devotion to international peace and diplomacy. Both men, especially Mr. Pearson, are renowned in the Canadian imagination for their devotion to the institutions of global governance, especially the United Nations, but Mr. Chrétien made it clear that they saw NATO as a complement, not an obstacle, to the multilateral institutions striving for world peace.

The former prime minister’s remarks comported with one of the NATO Association’s salient messages – that world peace cannot be secured with good intentions alone. It requires a failsafe mechanism, a constabulary agent that can enforce the rules of international order when their legitimacy is challenged from outside the normative diplomatic channels designed to redress them – most commonly, through armed aggression. Being able to cope with these kinds of international “surprises,” Mr. Chrétien asserted, was NATO’s raison d’être.

When it was Mr. Chrétien’s turn to occupy the office of prime minister of Canada, his tenure lasted during a watershed period in NATO’s evolution, when the purpose and mandate of the organization were moulded and shaped in the crucible of a succession of international incidents, crises, and conflicts. The conflict in Bosnia has already been mentioned, but one of the other contingencies Prime Minister Chrétien had to engage with, along with other NATO leaders, was the issue of NATO enlargement after the collapse of the Soviet-dominated Eastern Bloc. Mr. Chrétien recalled that the course he and other Allied leaders eventually settled on was one that struck a balance between two extremes. On the one hand was the potential for an overly zealous expansionism that would see the rapid enlargement of the organization, perhaps even to the point of including Russia. On the other was a wholesale avoidance of welcoming new states into the NATO fold for fear of any potential “instability” that such a policy might engender. The result was the phased, prudent enlargement of NATO, beginning in 1999, to incorporate select Eastern European states. Mr. Chrétien appeared to exhibit a feeling of vindication and satisfaction over that decision in light of current events, adding “the people of the countries that joined must be very happy today.”

In many ways, Mr. Chrétien’s policy, and that of NATO during this time, was one that steered a course between cold realpolitik and a naïve internationalism that, in the words of John Quincy Adams, goes abroad “in search of monsters to destroy.” No incident showcased this middle course better than the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq and Mr. Chrétien’s refusal to affiliate Canada with it. Had the invasion been authorized by the United Nations, or had it been launched in response to the invocation of Article Five of the North Atlantic Treaty, Mr. Chrétien asserted, he would have had no hesitation about Canada’s participation in the conflict. Mr. Chrétien said that while he pressed the Bush Administration for evidence that Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, he averred that “there was not enough proof to convince the judge at the municipal court in Shawinigan” that such weapons existed. Prime Minister Tony Blair’s moralistic entreaties to Chrétien to consider the depravity of the Saddam Hussein dictatorship as justification enough for his removal likewise failed to persuade his Canadian counterpart to change his view.

Twenty years after the events leading up to the Iraq War, Mr. Chrétien still appeared leery of Canadian involvement in foreign conflicts. When Ms. Rosiers asked him what Canada should do in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Mr. Chrétien responded by opining that Canada “cannot do much more” than it already has done, aside from opening its doors to Ukrainian refugees. If nothing else, his apparent discomfort with the idea of Canada playing a more assertive role – especially a military one – in the conflict in Ukraine, even under the immense moral pressure of Ukrainian pleas for assistance, demonstrated a consistency of mind that many in the auditorium would remember fondly as that disposition that kept Canada out of a war that even most Americans, retrospectively, see as having been a mistake. However, there were doubtless others in the audience for whom this cautiousness, in the face of the daily images of Ukrainian suffering, would have fallen short of their expectations.

Cover Image: Photo by author. Globe and Mail Centre. March 15, 2022.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.