Dear Justin,

As you work into the new job, you will probably be amazed at what a huge chunk the handling of foreign relations and defence takes out of your time and energy. It came as a complete surprise to your predecessor, as he admitted early on. But it is the same for almost any national political leader anywhere. The Canadian exception that proves the rule is probably Louis St Laurent, who had little time or interest, but he also had Mike Pearson who had a career in the foreign service before entering politics and, when he wasn’t inventing peacekeeping (strictly, be it said, in the interests of keeping the Western Alliance from falling apart over Suez), was also an extremely capable all-bases-covered foreign minister. You’ll probably find that whomever you appoint, you can’t quite deputize to that extent even if you want to.

The world has changed since those days. It was always more complex than simple bipolarity, but the nuclear rivalry of the superpowers had its own way of simplifying issues, mainly by constricting room for manoeuvre within the system. Canada never quite punched as far above its weight as legend would have it, and unkind reality (in the form of rude reminders like “You pissed on my rug!” from LBJ) had a habit of popping up at inconvenient moments. That still happens; it is usually unwise to tell a US leader on his own turf that anything is a ‘no-brainer’, especially when he himself may not see things from quite that angle.

The other day, the Old Man told you: ‘talk to everybody’. Wiser words were never spoken, especially in foreign policy. Sometimes embassy doors must be closed, but by and large, unless the closing is done in the face of dire imminent threat, the more they stay open the better. Canadian diplomats have their affectations, (who doesn’t?), but given support from Ottawa and a little freedom of action, there is nobody better on earth at working effectively in the quiet places of power.

You have a lot of lost time and ground to make up for and some strong currents to battle, a few of which of which may not be readily apparent. But from the point of view of working ‘the quiet places,’ one of the most important tools in the diplomat’s arsenal was always a foreign policy that at least made an effort to look like what it claimed to be. Low-profile was key. Your policy might not differ a lot in substance from someone else’s, but being actively strident has a substance all its own, usually unhelpful. Even the big guys find that out eventually.

One of the things that will drive you crazy, if you let it, is that you will never achieve consistency in foreign policy no matter how long you remain in office or how hard you try. There are too many moving parts and too many conflicting interests. You want to trade with China but their human rights record is inconvenient? Good luck squaring that circle – keeping their more underhanded business practices to a bare minimum in Canada will be enough of a victory if you can do it. Likewise with shoring up a regional economy via arms sales – it is an unfortunate fact of life that munitions, like any other commodity, need markets, and some of the best markets are the most repellent regimes on earth.

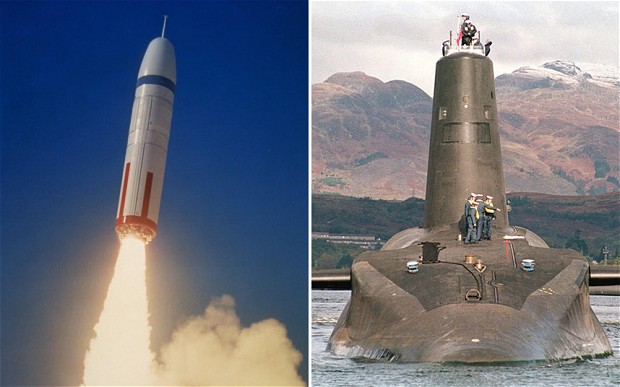

Probably the most obvious foreign relations problem that faces you is the need to back up ‘principled’ hostility or disagreement with substantive action. This avoids certain skewing effects, as for instance the commitment of six CF-18s to Iraq/Syria in a combat mission, and 70 Special Forces in an allegedly non-combat one. (Historically, if one part of a nation’s armed forces was at war, the rest were as well, as was the nation itself; the current stance seems to be a product of equal parts some of the more arcane War Studies conflict doctrines and wishful thinking — but that’s somewhat beside the point.)

The point is that if we had committed more forces in the first place, the decisions facing you might be a good deal more cut and dried, in the sense that a six-pack of CF-18s is symbolic force but not highly significant unless employed far more intensively than it has been, whereas two six-packs — about all we can manage without degrading our NORAD commitment — would have been significant enough to make any symbolism moot.

But I’m eager to know your rationale for pulling out the airpower but not the foot soldiers, yet to stay in the Coalition (I’m also glad that you left yourself some wiggle room in the conversation with Obama, whose official record of the conversation quite interestingly doesn’t mention the point at all). For one thing, those foot soldiers are Special Forces, and whatever the mission statement may say, it is very possible that their real role is a good deal closer to combat than you may be comfortable finding out. Informed American commentators have mentioned from time to time that Canadians are doing things that the US actually hasn’t yet been able to do itself because of the ‘no boots’ veil.

But even that is not quite the point. The point is that, as long as we are in the coalition at all, we are belligerents by association and by pretending otherwise we risk evoking John Manley’s old chestnut that ‘when the waiter brings the tab, Canada goes to the washroom.’ The Afghanistan commitment aside, that shot was always too close to the bows for comfort under governments of any political stripe. Honesty about actual contribution beats dissimulation, but actually paying up when the tab comes is a great deal better.

We are not a great power. Nobody expects us to be a great power. But the least they can expect is that our deeds match our words.

There is an argument out there that by bombing we invite reprisal in kind. I beg to differ. By involvement alone we invite reprisal, and disinvolvement might not spare us. But even if ISIS were interested in directly attacking us through anything but ‘motivational’ propaganda of atrocity — there is little evidence that they are and a great deal to the contrary — the theology of whether or not we’re there in a combat role is not going to weigh with them one bit.

Civilian casualties likewise. ISIS is not in the slightest concerned about civilian casualties; we are. Even Airways, the journalists’ organization that is trying to tally these things (and I hope they will begin to try tallying casualties inflicted by other parties as well) understand that in war there will be civilian casualties. It is the transparency or lack of it that is at issue – it is hard to refute allegations on the basis of no information. As I write this Canadians will have had no media briefing since early July – before the Russians came – and that is no way to fight a war in a democracy.

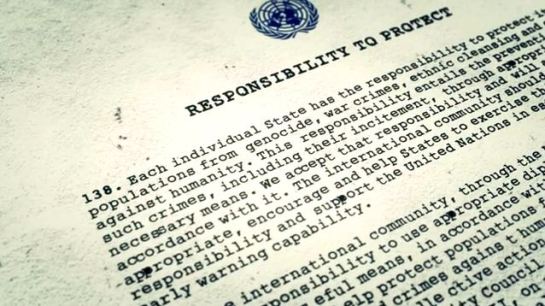

There is also the subject of the United Nations and whether it can still serve as a touchstone for the legitimacy of military action. Canada should not have spurned the UN root and branch. It furnishes far too many opportunities for interaction in ‘the quiet places’ and good deeds within our reach as a small-to-middle power. On the other hand, relying on it as the only legitimizing authority for multilateral military action is frankly a delusion that we as a nation have to get over. Those days, if they ever existed, are dead. They died on the day in July 2014 when Putin’s man Churkin stood up in the Security Council and brazenly told the world that from now on Russia would ignore the rules of an international system that by then was quite possibly waiting to be kicked over.

They may have died even earlier than that, when the UN deputized NATO to act as its implementing agent in Libya. Whether that or the alleged ‘regime change’ that the mission turned into – could it really have ended any other way given that it was never an R2P mission in the first place? – is what terminally offended Russia and China will be worth many a PhD thesis. But in the current state of international relations, making military action contingent on UN approval looks dangerously close to a blanket cop-out.

‘Talk to anyone’, indeed. But when talking with friend Putin, listen more to what he does than to what he says, as he tends to construct reality to suit his needs of the moment. It is ‘interesting’, if you can use the word about anything so indiscriminately deadly, that his aerial adventure in Syria seems so far to be validating the more cautious US strategy (it may be the bumbling product of a bumbling Administration, but I continue to maintain that it is a strategy) of waiting until local forces are willing and able to do the job. For a generation if need be.

Putin is bombing almost anything but ISIS, and though the Syrian rebels are taking casualties, Assad’s army at this point seem to be grinding itself to pieces against them, probably to ISIS’s collateral benefit, In the meantime, ISIS is showing no significant gains in Iraq, and the ground fighting in either theatre should be a signal warning to the West (and Russia) not to commit ground forces, though the temptation seems to be becoming harder to resist for the US at least. (Putin does not have to commit ground troops. As usual, he has the political advantage of manoeuvre; he can throw Assad under a bus any time he likes, and try another play elsewhere if he is prepared to swallow the regional costs of losing Assad as a political stalking horse.) ISIS may be an eventual threat to Russia, but in the short term it’s too handy a dumping ground for his own extremists for him to bother about more.

But these strategic niceties are less Canada’s problem than we are probably comfortable believing. ‘What do we do about Failed State X?’ is hubristic given Canada’s position in the world — who’s this ‘we’?? — but take some comfort that most of that talk is equally hubristic in Washington or Moscow. Failed states have an uncomfortable way of ‘doing about’ themselves by themselves no matter what anyone else wishes.

Always talk to anyone, but in this particular situation, and with our particular capabilities I’d listen to the Kurds. They’re not happy about us pulling out and they’re saying so. As effectives against ISIS, they are what we have and they’re good. (They’re also uncomfortably factional.) But they’re also not the sort to draw fine distinctions between combat and non-combat roles and in those parts – in most parts, for all of that – the deed speaks louder than the declaration.

Still, it all comes back to one thing: (a) regardless of how we define the granularity of our role, we are voluntary members of a coalition at war. Therefore: (b) no matter how we or any of the other caveat-holders try to spin it, as long as we are members of a coalition at war, we are at war. In the eyes of most Canadians, whether they’re for it or against it, that’s a little hard for a government to talk its way out of.

Keep talking, indeed, to everybody. But don’t let that get in the way of your and your allies’ interests, and don’t let your guard down for a minute. It is not a bright epoch that we live in, and seemingly becoming darker.

Yours sincerely, and best of luck,

Eric Morse