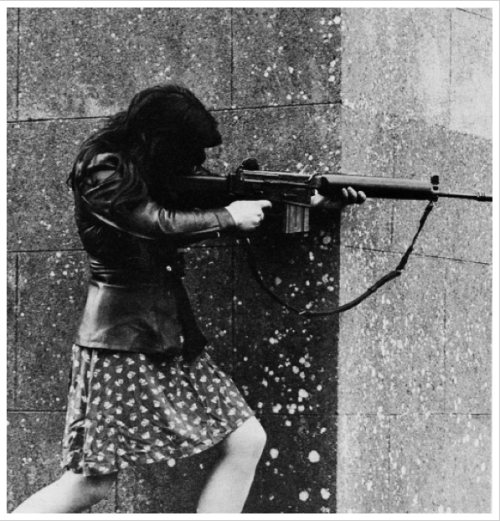

[captionpix align=”right” theme=”elegant” width=”400″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/South-Africa-Mine-Vio_Bake.jpg” captiontext=” Police opened fire on striking miners at the Lonmin Platinum Mine in South Africa, Thursday, Aug. 16, 2012. (AP Photo/AP2012)

“]

The violent culture in South Africa is contaminating its economy. Last year, over 50 people were killed in labour-related violence. The worst incident involved police officers killing 34 striking miners at Lonmin’s Marikana’s platinum mine.

While President Jacob Zuma downplays the effect of both last year’s strikes and this year’s labor instability, the reality is that crime and violence in South Africa has gone unaddressed for too long. Social, political, and cultural destructive patterns are threatening South Africa’s mining industry.

A Socio-Historical Explanation: Breeding Grounds for Violence

South Africa has one of the world’s largest crime rates. In 2010, World Cup travelers were wary to go to a nation where every year there are 18,000 murders and 18,000 attempted murders. Crime seems to be a common outlet. People take what they think they deserve, or merely decide it’s easier and more profitable to attain their livelihoods illegally. Because of the inefficiencies of the South African Police Services (SAPS) and the justice system, some communities have resorted to mob justice. This recourse is problematic because foreign nationals are often targeted and action can take place without any evidence that proves an individual guilty of a crime. Despite the SAPS increasing in number by 65% from 2002 to 2012, they are not more efficient or less partisan to ethnic and political ties. The SAPS have a legacy of torture and are often feared and mistrusted by communities, which in turn undermines their efficacy.

In South Africa, after the success of the African National Congress (ANC), people expected more to change after liberation than is feasible in the immediate aftermath of drastic political restructuring. After decades of colonial oppression, South Africans expect wealth to change hands, living conditions to change, and politicians to be accessible, all within a short timeframe. However, people quickly became disillusioned. They saw that the promises of politicians did not align with their actions, even when these politicians speak their language, share their culture, and suffered under the previous leadership alongside them.

The ANC warned its people that it would not be able to resolve the situation immediately, and that change should be expected to occur gradually. However, people remain frustrated with the fact that wealth remains in the hands of the few. After disappointment with the government, people turn to violence as a fast way to boost their livelihoods, but crime leads to bitterness, grudges, and the use of force upon the nation.

Future for South Africa’s Mining Industry: Zuma- No Big Deal, Right?

The South African economy relies on mining. Throughout its history, South Africa has emerged as a major source of various minerals, and has established itself as the world’s largest platinum producer. The mining industry accounts for 60% of South Africa’s export revenues.

Despite President Jacob Zuma’s efforts to alleviate fears of labor unrest in South Africa, there has been a decisive change seen in the mining sector. There are increasing claims that politicians are not transparent in their dealings with the international community. The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) is speculated to have close political ties to the ANC. This calls into question their political neutrality, and the way that the ANC reacts to illegal strikes. Rewarding violence or making violence acceptable can set dangerous precedents, as the NUM Secretary General Grans Baleni stated. The ANC has not adequately dealt with the violence from both the police and protestors during the strikes.

The South African economy has lost billions in lost output, and investor confidence is increasingly fragile. The Rand lost 10% of its value because of skepticism in the South African economy. Markets want to see more action and results on the part of the government, not more empty words. Business Against Crime South Africa made it their mission to support the government in its fight against crime. They are an example of an organization that acknowledges the effect of crime on business.

Last week Glencore Xstrata fired 1,000 workers in mines for an illegal strike. This mirrors the Marikana strikes where Lonmin argued that miners acted illegally and outside of the scope of the Labor Relations Act. On Monday, June 3rd, a miner from NUM was shot dead at the Lonmin mine, but the police do not know who is responsible for the attack. Again, this is an echo of the South African security and justice system. Many murders and acts of crime in South Africa remain uninvestigated or unresolved, and at present this mining official seems to fall into this category.

If the ANC intends to keep its promises of job creation and a better South Africa with opportunities for many, not merely the few, then the South African mining sector needs to become an attractive investment climate.

South Africa has incredible mining resources and economic potential, but the industry also requires sound management, oversight, constructive dialogue with unions, transparency in the situation, and realistic and strategic policy improvements. All of these are needed to make for an attractive and reliable economic climate for international investors.

Canadians have a significant stake in the stability in the region. Canadian mining companies increased their exploration of natural resources in South Africa, but fear of increased nationalization as suggested by populist politicians makes companies wary.

A strong economic sector cannot co-exist alongside corrupt and inadequate security and judicial systems. Unless policies change to keep people accountable for their actions, but also to open effective channels of communication, strikers will continue to use violence. As one worker at Marikana put it: “Violence works… When we just talk, we get only peanuts.”