Negative political advertisements face backlash as they are often attacked for contributing to voter cynicism and for being a form of manipulation. Individuals view negative ads as cheap methods to help win elections. In the 1988 presidential elections, George H.W. Bush used negative ads to beat Michael Dukakis. Despite being behind in the polls by 17 percentage points, Bush’s willingness to use attack ads and the unwillingness of Dukakis to do likewise contributed to the latter’s loss.

Although negative political advertising is seen as unethical, one cannot deny the benefits provided by this strategy. On average, political parties spend 30-50% of their advertising budgets on negative ads. This special report will explore the effect of negative advertising on the American political system by taking an in-depth look at its effects on turnout levels, the impact these ads hold on political views, their efficiency, and their benefits to democratic regimes.

Negative Political Advertising and Voter Turnout

In 1995, Ansolabehere and Iyengar’s report Going Negative: How Political Ads Shrink and Polarize the Electorate sparked discussion on the effects of negative political advertising on voter turnout. Ansolabehere and Iyengar concluded that negative advertising has a direct impact on voter turnout, arguing that exposure to negative television ads reduces the likelihood of voting by five percent when compared to those who watch positive advertisements. They further stated that negative politics causes a reduction in political participation and is responsible for a decline in political interest.

As a direct response to Ansolabehere and Iyengar’s paper, David Niven published his report, A Field Experiment on the Effects of Negative Campaign Mail on Voter Turnout in a Municipal Election. Niven aimed to replicate Ansolabehere and Iyengar’s data in the real world, in contrast to Ansolabehere and Iyengar, who had performed their experiment within a lab setting.

Niven performed his experiment during the 2003 mayoral election in West Palm Beach, Florida. Niven selected a random sample of 1400 eligible voters, placing 700 in a treatment group and 700 in a control group. Preceding the election, the treatment group received daily negative ads targeting the incumbent mayor; either a single day, two days, or three days prior to the election. The ads took three forms: issue-based ads (Type A), personal and issue-oriented ads (Type B), or personal attack ads (Type C). The advertisements were sent on behalf of “People for Responsible City Government.” After the elections, Niven conducted a follow-up survey to determine if there was a linkage between negative ads and turnout.

Niven produced three separate models whose results demonstrate the benefit of negative ads. Niven’s findings show that those who receive negative advertisements are 1.44 times more likely to vote in comparison to those who do not receive exposure to the negative ad. Those who demonstrate a pattern of consistently voting in the past are 10.26 times more likely to vote when exposed to negative advertisements. Niven also found that one negative ad does not have a significant effect on voter turnout, however, two and three ads do. As exposure to negative ads increases, the turnout rate increases – by 33.7% for two ads and 36% for three ads. When analyzing the effect of the ad type, issue-based ads produce a lower turnout. Personal attack ads that attack the decisions and actions of the incumbent seem to mobilize the population to vote. Type A ads produce an insignificant effect on voter turnout, whereas recipients of type B are 1.3 times more likely to vote and type C recipients are 1.5 times more likely to vote.

Niven’s results demonstrate that negative advertisements can help simulate turnout. The field experiment shows that recipients of the negative ads have a higher chance to vote than those who are not exposed to negative ads. This is in direct contrast to the results Ansolabehere and Iyengar produced in their lab-based experiment. Negative ads are often labelled as unethical, however, their ability to mobilize the public makes them favourable in the eyes of political parties. According to Niven’s post-election survey, ad recipients are more likely to state they are informed about the candidates after viewing negative ads. They also are more likely to state that they care about the outcome of the election. In this sense, negative ad recipient responses demonstrate a higher level of political interest and activity than those who receive none.

Impact of Negative Political Advertising on Political Views

Negative advertising is often argued as being harmful and eroding American politics. Political scientists argue that negative advertising results in eroding effects and breeds cynicism within the masses. In one study, Robert A. Jackson, Jeffery J. Mondak and Robert Huckfeldt explore the effect of negative campaigning on the 2002 U.S. midterm elections. Utilizing political ad data from the Wisconsin Advertising Project and the 2002 Exercising Citizenship in American Democracy Survey, they conduct an experiment to test if exposure to negative ads results in citizens holding cynical views on politics. They tested for relationships between ad tones and individuals’ perspectives of the political systems; the effect of negative ads on partisans and independent voters; the effect of negative advertisements on those of low and high political knowledge.

Jackson, Jeffery, and Huckfeldt categorized the advertisements on a five-number scale from pure attack ads to pure promotional ads to see the effect of different tones in political advertisements. When analyzing the results, one does not see a pattern supporting the claim that attack ads create cynical views of politics. Their model also demonstrates that the negative tone of attack advertisements does not lower the level of Congressional approval or impact citizens’ perceptions of Congressional performance. According to this study, the bombardment of negative ads citizens face during elections does not result in the formation of pessimistic views of the government and politics.

When analyzing the effect of advertisement tone on nonpartisan voters, one finds no values of statistical significance. Nonpartisan and independent voters’ approval of Congress and perception of government are unaffected by negative political ads. Jackson, Jeffery, and Huckfeldt reran their experiment to test for negative ad influence, based on respondents’ level of political knowledge. If individuals with low levels of political knowledge are susceptible to generalizing political judgement, one would expect that the effects of negative advertising must be most evident within the least knowledgeable. This is however not the case. The authors found no correlation between the level of political knowledge and the negative impacts of negative ads. Negative ads do not cause unknowledgeable individuals to develop poor images of the system. Therefore, negative political ads do not lead to the development of corrosive images within nonpartisan and politically uneducated individuals. In Jackson, Jeffery, and Huckfeldt’s study, no empirical evidence was found to support the theory that negative ads promote antipathy towards politics among this group.

The Efficiency of Negative Political Advertising

Political candidates spend 30 to 50% of their advertising budgets on negative advertising. The fact that parties dedicate large portions of their budget to negative political advertising, implies that they must believe it is effective. The efficiency of negative ads is an area of constant study. Previous studies showed that individuals recall negative information more easily, with Johnson and Copeland’s survey, for example, demonstrating that two-thirds of respondents recall seeing negative advertising. Because negative ads are not the norm, individuals are not accustomed to seeing them, making their messages stand out. Though they are an effective tool, one must be careful when utilizing negative ads for they can also backfire.

The effectiveness of advertising varies based on the attributes of the ad and attributes of the voter. Negative ad attributes tend to have varying impacts on targeted individuals. Garramone finds that negative ads tend to have a larger effect if they are sponsored by a third party, rather than opposing candidates. Negative ads with strong emotional impact and visuals tend to be easily recalled by citizens. Political advertisements that tend to attack decisions made by incumbents and their positions on certain issues tend to be more acceptable than personal attacks. Personal attacks lack effectiveness and lead to backlash. Voter attributes such as partisanship tend to have the greatest effect on decoding negative advertisements. The greatest impact is evident within the partisans of the attacking party, however, the opposite is true for supporters of the target; negative ads tend to create backlash among these audiences. Voter involvement and level of interest in politics may also impact reactions to negative ads.

In Negative Political Advertising and Voting Intent: The Role of Involvement and Alternative Sources, Ronald J. Faber, Albert R. Tims and Kay G. Schmitt tested to see the impact of negative ads on voters in terms of their level of political interest. The authors focused on two types of involvement: enduring and situational. Enduring involvement refers to a long-term interest, whereas situational is a temporary concern with an outcome. In this test, enduring involvement refers to how closely individuals follow politics and situational involvement refers to the interest in the outcome of an election. Faber, Tims and Schmitt hypothesized that negative ads will have a positive impact on individuals with enduring and situational involvement, however, individuals with situational involvement will experience a greater influence. They also looked at sources of political information to determine how these would impact negative ad influences. They hypothesized that individuals who rely on newspapers will have little to no impact from negative ads, but that those who seek the news on television would be influenced by negative ads. The basis for the hypothesis is the authors’ understanding that newspapers utilize large levels of reasoning and knowledge, whereas television is associated with lower levels of information.

Faber, Tims and Schmitt used the 1988 Minnesota U.S. Senate Race as the basis for their research. Ten days prior to the elections, they conducted a telephone survey, asking respondents if they recalled seeing specific negative ads. Respondents were then told to rate how likely they were to vote for the targeted and attacking party based on the negative ads. Using questions regarding how often individuals discussed politics and their political involvement, they determined individuals’ levels of situational and enduring involvement. Using a correlation matrix, they then analyzed the influence of negative ads.

The results confirmed the authors’ original hypothesis; enduring involvement and situational involvement are both positively correlated with negative ad impact. A positive correlation states that both variables move in the same direction. As an individual’s enduring and situational involvement increases, so does the impact of the negative ad. Situational involvement is more highly correlated with negative political ad effects, meaning situational involvement has a greater impact than enduring involvement. Individuals who rely on television-based news media tend to be positively impacted by negative ads, unlike newspaper-reliant individuals. Newspapers and negative ads do not have a significant correlation, meaning the impact is null or very minimal. The correlation matrix results are further supported by Faber, Tims and Schmitt’s regression model.

Individuals may believe that those who tend to follow politics closely do not fall victim to the influence of negative ads due to their wider array of knowledge. However, this research shows that negative political advertising has a greater impact on those who demonstrate higher levels of enduring and situational involvement. One hypothesis suggests that this is due to the possibility of less engaged citizens paying less attention to political media, including negative ads. As a result, politically-engaged individuals are more likely to be targeted by all forms of political media. Politically-engaged individuals are also more likely to be partisans. During the process of picking sides, their attachments make them more reactive to negative ads. These individuals are likely to react when their party is attacked and support attacks on opposing candidates.

An Optimistic Perspective on Negative Ads

Negative political advertising often faces criticism and is attacked for its unethical ways. Although many view negative ads as corrosive, they have many positive functions. Political parties aim to manipulate and shape issues to best suit their political brand. The goal is to shape debates in the news to focus on areas where the party has an advantage. Negative advertising, when used correctly, can poke holes in superficial images and help shift focus away from image politics. Negative ads provide alternative perspectives to help voters analyze politics from other angles.

Negative advertising benefits democracy as it often presents more factual information than positive advertisements. Negative ads may highlight concerns in opposing party policies and play a watchdog role. Positive ads are constructed to avoid hard policy questions and rarely provide valuable information. They are often not aligned with reality and showcase the sunny side. Negative ads may be unpleasant, but they often help uncover hidden truths. Information in negative advertising also benefits democracy as it contributes to effective citizenry. Brians and Wattenberg’s survey data demonstrate that individuals who watch negative advertising are more accurate at depicting candidates’ positions on issues. These citizens demonstrate a more accurate assessment of political candidates than those who rely on newspapers. The information in negative ads is also highly beneficial during elections, where candidates often have similar ideas and positions. Negative ads help differentiate between candidates. When challenging incumbents, negative ads help the underdogs and are often necessary. These ads promote good government as they highlight concerns in opposing party policies. To conclude, even unethical measures can have positive outcomes. Individuals often look at negative ads through a pessimistic lens, however, the benefits to democracy are great. Negative ads may not be so negative after all.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.

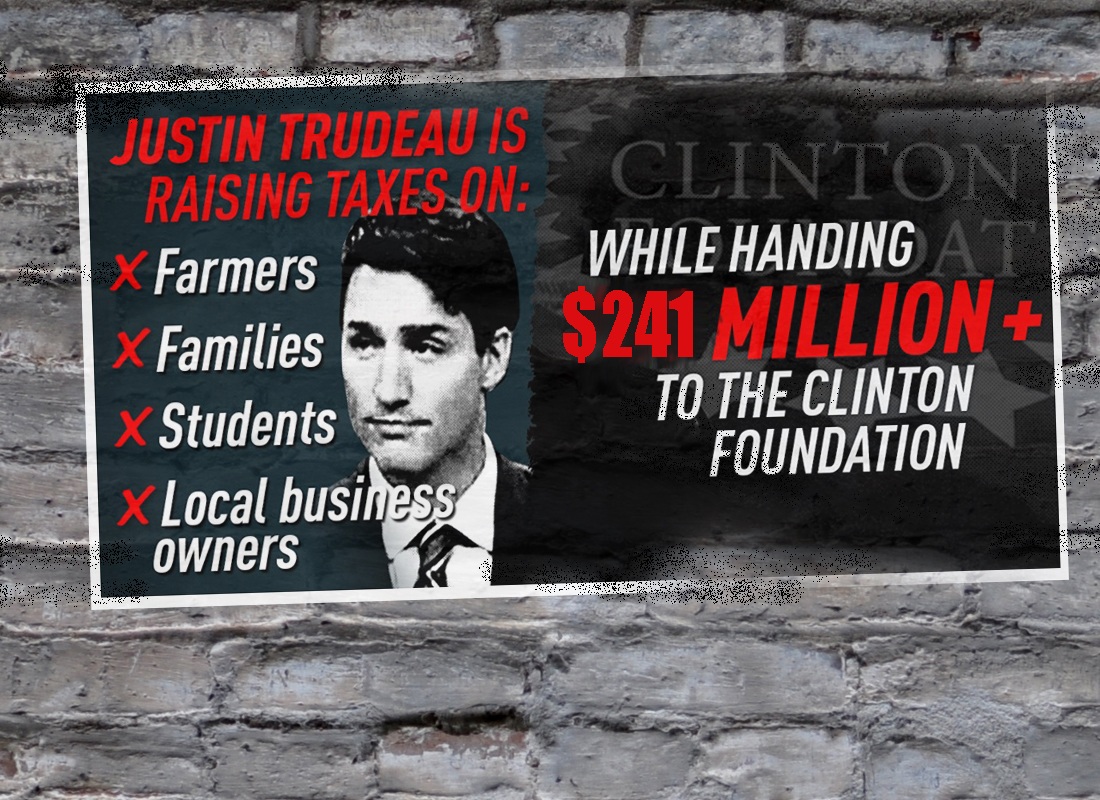

Photo: an attack ad on Justin Trudeau by Sklokapus (2018) via Flickr