Over the past twelve years the United States alone has invested over $126.5 billion in Afghanistan’s reconstruction effort. However, as the former British Ambassador, Sherard Cowper-Coles states, none of those funds has bought the international community or Afghans many sustainable institutions or programs. It follows that with the overall lack of progress made in state capacity combined with just a few months left in which NATO forces will officially be involved in the Afghan military effort, the insurgents have few incentives to engage with an outside power that still does not seem serious about rebuilding the country or incorporating them into any political settlement. With a complete lack of political stability or capacity within the country, particularly in the outlying provinces, handing over these districts to Afghan forces upon the NATO departure is unlikely to stabilize the country in any sustainable way. In these situations ‘transition’ sounds more like a way of marketing withdrawal.

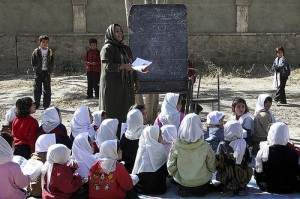

John Warnock argues that in failed states, and more specifically Afghanistan, legitimate, stable and sustainable governmental capacity takes years of patience and hard work to build. However, this has been systematically undermined by the plethora of donors at work in Afghanistan as they continued to fund programs and projects that would directly benefit the population without consulting the proper ministry within the Afghan government. This creation of a parallel provision of services is often evident in the post-conflict reconstruction of the education sector, and it is no different in Afghanistan. While external governments have been slowly building capacity in the education ministry in order to provide pay to teachers and draft a new curriculum, they also circumvent this channel to ensure they create short-term successes as well, such as the building of schools or the provision of textbooks and technology on an ad-hoc basis. With training local officials often a long and tedious task it is very tempting, and often more rewarding, to do such projects yourself, but as a consequence a parallel donor bureaucracy is developed which undermines the legitimacy of state ministries and diminishes state capacity in the long-term.

“Abandoning Afghanistan at this stage of development is not an option…In order to secure our interests we must first secure theirs.”

A large part of the fascination of working in and on Afghanistan is the astonishing range of international actors with an interest in the country, stretching far beyond the nations contributing to the NATO-led, American dominated International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) however, the overwhelming number of actors is, in fact, the main pitfall in capacity-building initiatives as no one can effectively agree on strategy or focus. Francis Fukuyama addressed these issues stating that, “the contradiction in donor policy is that outside donors want both to increase the local government’s capacity to provide a particular service, and to actually provide those services to the end-users. The latter objective almost always wins out because of the incentives facing the donors themselves” back home.

With this in mind it is naïve to expect not only reconstruction to flourish but for reconciliation occur and government capacity to increase on any significant level in the absence of an overarching political, economic, social and military strategy, both for Afghanistan and the international actors involved in its development. Government, and more importantly local Afghan ownership is critical to the establishment of a prosperous, secure Afghanistan. But, as Ashraf Ghani stated, while the people and government of Afghanistan are fully committed to seeking partnership in this process, it must be considered “a partnership of equals” with the interests of Afghanistan and its development taking priority over Western incentives.

As Nigel Fisher of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan notes, a “failure to invest in Afghanistan at this critical juncture could help to fulfil our worst fears of the integrity, the economic development and the unity of Afghanistan.” With the remainder of NATO forces slated to return home this year the development project in Afghanistan is at a crossroads: countries will either reinvest in securing the country in order to ensure their own security or allow history to repeat itself. Abandoning the country, especially at this stage of development is not an option. After nearly thirty years of acting as an imperial plaything, the re-abandonment of the country will dissolve any capacity that had been built and add fuel to the anti-American ideological fire already burning throughout the region. As Human Rights Watch’s James Hoge says, “If we weren’t doing what we’re doing, the question is, would things be better, or worse for Afghanistan?” The only option to ensure that Afghanistan continues on a stable, sustainable development path, and to maintain international security, is to re-evaluate our progress, learn from our mistakes and with an understanding that in order to secure our own interests, we must first secure theirs.