In the wake of the terrorist attacks in Paris, refugees escaping Iraq and Syria have become a global political target. To protect the US from foreign terrorism, Republican presidential candidates have suggested refusing non-Christian refugees, shutting down mosques, and creating a mandatory database that would track Muslims in America the same way FedEx tracks packages. And it’s not just Republicans: 47 Democrats voted in favour of a bill that will effectively halt refugee arrivals from Syria and other Islamic nations, which was approved in the House of Representatives by 289 votes to 137.

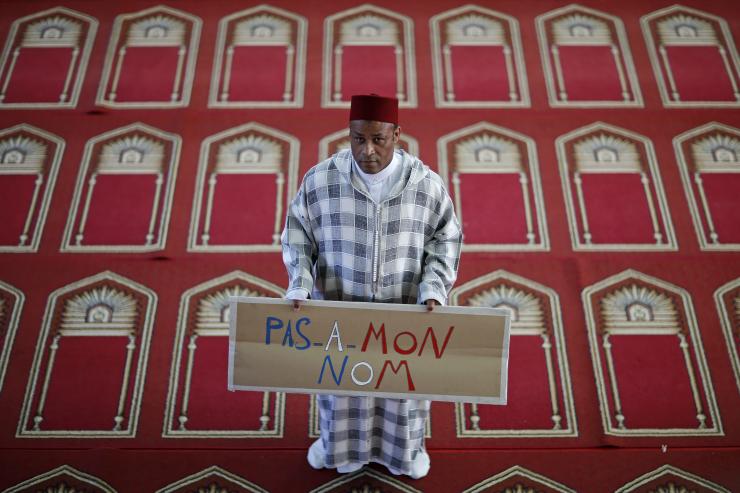

Similarly, Canadian premiers urged Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to reconsider bringing 25, 000 Syrian refugees to Canada before the year ends in the name of safety and security. Anti-refugee and outright anti-Muslim nations in Eastern Europe have also toughened their opposition to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who now faces immense pressure to halt the flow of refugees entering the EU. On the ground, even diverse and cosmopolitan cities like Toronto, London, New York, and of course Paris have all seen an immediate spike in Islamaphobia and violent hate crimes targeting mosques and Muslims. The idea that radical Islamist terrorists have infiltrated the streams of refugees pressing into Europe and North America has whipped up an international frenzy of fear and hysteria.

Research on the relationship between refugees and national security, however, stands in stark contrast to this current rhetoric. In fact, claims that refugees pose a significant risk to either national or international security are virtually baseless. Not a single one of the Paris assailants was a refugee, and neither were the Charlie Hebdo terrorists. In the US, not a single refugee who has gone through the refugee-resettlement process since the 1980s has committed a terrorist act in America. Of the 784,000 global refugees the US has accepted since 2001, only three have been arrested for any activities related to terrorism. Two men were indicted and jailed for plotting to send weapons to terrorist organizations in Iraq, while one man was convicted of terrorism-related charges for possessing explosives and supporting a terrorist organization in Uzbekistan. None of the three posed any credible domestic threat.

In Canada between the mid 1980s and 2005, 26 political extremists tried to enter the country by posing as refugees. Twenty-four were arrested during the screening process, and the other two fled the country after coming under indictment. It is worth noting that none of these 26 extremists was planning or coordinating an attack. According to Andy Lamey, a professor with expertise in terrorist refugee claims, Canada’s refugee system has not been used to plan or execute a terrorist operation a single time in the last 30 years.

Current refugee screening processes have proven to be highly effective because they are multi-layered and exhaustive. In the US, refugees are subject to the highest level of security checks of any type of traveler. In the case of Syrian refugees, claimants are first vetted by the UN in refugee camps along the Syrian-Turkish border before being referred to US officials. The US then conducts several in-person interviews with the refugee, verifies his or her personal history with intelligence agencies, and runs a background check through several databases including the Department of Homeland Security and the National Counterterrorism Center. Every cross-check is done in an effort to ‘poke holes’ in the refugee’s story and identify any potential inconsistencies or untruths.

American refugee laws, as they are currently interpreted and applied, are incredibly stringent. For example, in the case of Syria, many refugees have fled from areas that have fallen under opposition control. Under US law, if a refugee owns a food stand and US officials find that opposition fighters purchased falafel sandwiches from that food stand, the refugee would be found to have provided ‘material support’ to the opposition and his claim would be rejected. Moreover, a refugee found to have ‘supported’ opposition forces would be denied even if the US government supports the same opposition group that the claimant assisted. For instance, while the US military was protecting the Iranian MEK, a widow in Iraq who supported her family by working as a florist was denied resettlement because members of that group had purchased flowers from her shop.

Failing to properly socially and economically integrate refugees into host societies can lead to major security issues. Inefficient processing systems that leave refugees socially and economically isolated in refugee camps can acutely increase the risk of radicalization. During the Cold War, the extended displacement of young, uneducated Afghans in deteriorating conditions turned refugee camps into loci for drug and arm smuggling. Palestinian and Iraqi refugee camps, too, have presented an issue to international security as terrorists groups have recruited from them. According to Jill Goldenziel, a Research Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s International Security Program, there is a critical link between social order and terrorism. With their previous social order destroyed, depleting financial resources, continuing lack of economic opportunity, and few social integration mechanisms to assist them, some groups may mobilize within refugee camps to establish a social order of their own. Underpinned by fear, anger, and desperation, this can lead to the formation of radical organizations and extremist sects.

Insufficient social and economic integration causes radicalism to emerge not in refugees but in their children. Second-generation citizens from marginalized groups, like Arab Muslims, may face social isolation and a lack of economic opportunity in Western countries, which in turn fuels disillusion and resentment. Significant terrorist groups like Hamas and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), for example, grew out of the Palestinian refugee crisis of 1948. The second generation of ‘frustrated and politicized’ refugees faced “few opportunities to integrate into their host societies” and joined militant groups to gain a sense of brotherhood, belonging, liberation, and economic opportunity. Second-generation radicalism, ultimately homegrown, can be found in the Charlie Hebdo terrorists who were racially marginalized French-born citizens of Algerian immigrants. Similarly, the Tsarnaev brothers who carried out the Boston Marathon bombing were not refugees but the children of Chechen asylum-seekers, and became radicalized well within the walls of America.

As we accept some level of risk when driving a car or boarding an airplane, so too is there some risk implicit in accepting refugees. However, research denies that refugees pose any substantial threat to national security and public safety. Rather than focusing on those fleeing the Islamic State, we should focus our attention on the hundreds of Europeans and North Americans who have gone to Iraq and Syria to fight alongside them. It is that brand of homegrown radicalization, stemming from Muslim alienation and insufficient social and economic integration mechanisms, that should be informing the refugee debate. Accepting refugees is not the central threat to national security; it is what happens after they are accepted that matters.