On most lists of pressing national security issues for the 21st century, ethnic tensions, drugs, terrorism, or nuclear proliferation take pride of place. However, assessing security threats to Pacific Island states, one word appears that Western readers may find curious: tuna. In late July, I wrote an article about the importance of climate change in general security discourse and mentioned that climate change has an extremely wide variety of impacts on security globally. For the Pacific, in addition to other impacts such as sea-level rise and flooding, climate change is substantially impacting the distribution of tuna in the region. This is projected to take a significant toll on the economic and food security of several Pacific Island states. This article highlights the importance of tuna to the Pacific region.

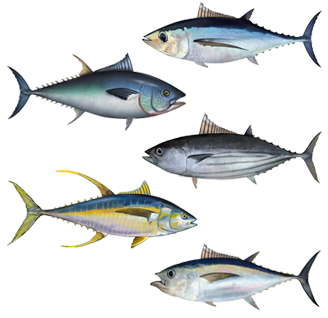

The Pacific Islands are a collection of countries or near sovereign entities differing in size, economy, and population. At one extreme, there is Tuvalu, with a population of 11,206 and a size of 25.9 square kilometers (Toronto is over 600km in size, for reference). At the other extreme, Papua New Guinea has a population of over 8.6 million and a size of 462,840 square kilometers. Yet all Pacific Island states are remote, and many are largely dependent on their marine resources for sustenance and revenue. Four species of tuna (skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye, and South Pacific albacore) are the most critical of all marine resources, and are presently found in abundance in many Pacific Islands’ exclusive economic zones (EEZ), non-territorial waters where countries retain economic rights to resources. In 2016, the combined harvest of these four species accounted for 30% of the global tuna catch. To monetize this resource, many Pacific Island states sell tuna licensing rights to foreign companies. Six Pacific Island states earn at least 45% of their government revenue from tuna fishing license fees, with the most being Tokelau with 98%. For reference, Canada receives 49% of its revenue from income taxes. The link between tuna fish and economic security in the region is inextricably entangled, as even non-tuna producing Pacific Island states have thousands of individuals employed in domestic tuna processing plants. Climate change jeopardizes this precarious position.

Two species of tuna, skipjack and yellowfin (the most abundant sources), enjoy relatively warm water. Climate change will inevitably increase the surface temperature of the ocean, and modeling predicts that the natural habitats of both skipjack and yellowfin tuna will shift eastward, away from the EEZs of many Pacific Island countries. Perhaps fortuitously, scientists can predict this effect with near certainty as eastward tuna movements have been observed during the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a meteorological occurrence where, simply put, Pacific sea temperatures warm in the eastern Pacific ocean on an irregular basis. When this occurs, tuna have been monitored shifting eastward, while shifting back during La Niña, the opposite phase.

Therefore, climate change will likely permanently alter tuna habitats, which will in turn have a grave economic effect on the nations who rely on the species for revenue or food. Fortunately, there are ongoing initiatives to help Pacific Island states adapt their tuna fisheries to climate change. For example, the Green Climate Fund is currently developing a project, in partnership with Conservation International, an environmental NGO, which employs a holistic approach to capture both the food security and economic aspects of the issue in eight Pacific Island states. The project is funding fish aggregating devices (FAD) to deter tuna from leaving country EEZs. At the same time, the initiative funds programs to increase the value of tuna by developing a more robust domestic tuna economy, allowing countries to make more money per tuna despite fewer tuna being present. The project also plans to invest in monitoring systems as well as capacity-building exercises for local fisherman to increase operational efficiencies.

This article highlights that though seemingly negligible to security on a global scale, tuna has a substantial impact on livelihoods in Pacific Island states. This reflects the omnipresence of climate change, fact readers of this article may now remember when having their next tuna sashimi, tartar, or melt.

Photo: Assorted tuna species (2012), by NOAA via NOAA’s Fishwatch. Public Domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.