“One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”. The increasingly popular phrase seems simple, but its complexity is undoubtedly the source behind the failure of the international community to agree on a definition of terrorism. The governments of the world have attempted to find an all-encompassing definition of terrorism for many years without any success. This indecision has resulted in dysfunction within the United Nations, as progressing towards combating terrorism is difficult to do when you cannot define what you are attempting to combat. Until a functional definition of terrorism can be found that suits all parties, politicians and scholars will continue to produce definitions that encapsulate all of the necessary elements of defining terrorism, but do not cater to the desires and beliefs of all parties.

“The trick has been to find a definition of what we’re trying to prevent, while at the same time acknowledging that the legitimate aspirations of people yearning to be free are sometimes expressed in ways other than bargaining in a three piece suit”

Terrorism, as we commonly understand it, has proven to be a global issue, and thus, it should be managed from a global perspective. Without a commonly accepted definition of terrorism, major strategy operations cannot take place at a multilateral level; instead, nations are forced to handle the issues related to global terrorism from a domestic position, which is much less effective in dealing with something global in scope. Currently, multilateral institutions cover a wide range of terrorism related strategies, including; sanctioning, intelligence gathering, law and policy implementation, international financial controls, and various other multilateral frameworks with the intention of limiting international terrorism. However, the question remains, what is making definitional solidarity so difficult at this level?

Even with all of the parties and tools in place to combat terrorism, the United Nations has not, will not, and cannot agree on a commonly accepted definition. The reason for this widespread inability can be attributed primarily to diversity. Diversity is what most would consider as one of the more advantageous characteristics of the United Nations; however, it has unarguably hindered the process of definitional solidarity.

The United Nations is such a large and diverse body that issues such as terrorism affect each member of the United National differently. This is important to note, as terrorism may be high on the priority list of states like the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, but for some, terrorism is not a priority at all. To put this into perspective, one must understand that there are far bigger security threats to states than terrorism, especially those detached from the current Islamic fundamentalist conflict in the Middle East. Nations in Africa, for instance, are subject to security issues such as droughts, famine, and disease. Currently, terrorists have little to gain from attacking these regions. Moreover, terrorism is not much of a concern in many places.

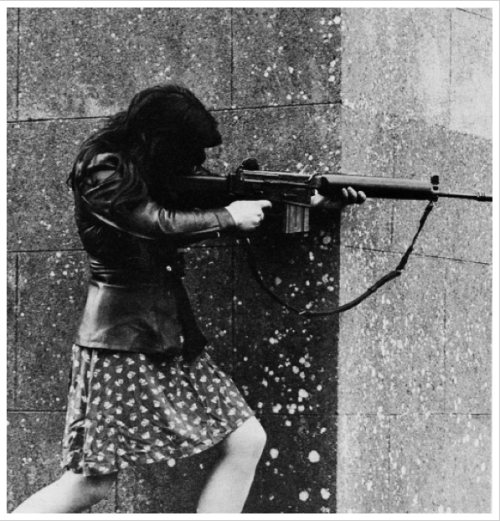

In addition, United Nations member states that are exposed to the threat of terrorism have a different understanding of the phenomenon, as what one state defines as a terrorist, another state would define as a freedom fighter. Nowhere is this more evident than with the Irish Republican Army in the 1970’s. The United Kingdom considered the Irish Republican Army to be a terrorist organization, as their tactics were indicative of what the British thought to be terrorism, however, these feelings were not replicated completely by the Republic of Ireland, who saw the efforts of the Irish Republican Army to be indicative of a fight for freedom and unification of Ireland, and thus, the Republic of Ireland supported their early efforts to varying degrees.

In 2004, the United Nations came extremely close to constructing and agreeing upon a suitable definition of terrorism. The United Nations Report of the Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Threats Challenges and Change proposed that terrorism should be defined as;

“any action, in addition to actions already specified by the existing conventions on aspects of terrorism, the Geneva Convention and Security Council Resolution 1566 (2004), that is intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to civilians or non-combatants, when the purpose of the act, by its nature or context, is to intimidate a population, or to compel a Government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing an act”.

The United Nations attempt to define acts of terrorism was promoted vigorously by the Secretary General at the time, Kofi Annan, who called on the governments of the world to come together for the production of a universal convention on terrorism, in an attempt to tackle it more effectively. Criticism of the plan was high since its inception, however, despite the proposed definition’s inconsistencies and shallow nature, Allan Rock, Canada’s ambassador to the UN at the time, said that Kofi Annan’s proposed definition may not be ideal, but it is a good working start. Mr. Rock went on to say; “The trick has been to find a definition of what we’re trying to prevent, while at the same time acknowledging that the legitimate aspirations of people yearning to be free are sometimes expressed in ways other than bargaining in a three piece suit”. Furthermore, it appears that until a definition can be found that is inclusive of all parties, agreement on a global scale will be delayed.

With the overwhelming diversity of the United Nations taken into consideration, it is no wonder a definition cannot be agreed upon. Regional multilateral institutions, like NATO, and the EU are more likely to overcome this diversity and agree upon a working definition of terrorism, as these regional bodies are likely to be less diverse, and experience similar security issues, thus making definitions slightly easier to agree upon.