[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=”http://www.fco.gov.uk/content/en/travel-advice/sub-sahara-africa/mali/749677882″ captiontext=””]

The head of the African Union is petitioning NATO nations to send forces to Mali to expel Al-Qaeda-linked fighters, who have overtaken the north of the county. He warned that convoys of Islamist extremists advancing on government-held towns represent a looming threat to the world.

Without a moment of hesitation, the rhetoric of quixotic interventionism for Mali sprang-up in major Canadian newspapers across the nation. Interventionists, such as former ambassador to the United Nations, Robert Fowler, advocate for the Harper government to intervene in Mali and put an end to Al-Qaeda and its allies. It is true the threat of jihadist takeover of northern Africa is very real and could pose a threat to the stability of the northern region of Africa―turning it into a chaotic and ungovernable zone. However noble an idea, given the domestic climate in Canada―student unemployment, fragile economy, an ever increasing income gap, and aboriginal poverty―it would be unwise for the Harper government to intervene in Mali.

The prescient Munich analogy―taking care of the world and the lives of others―does not take into consideration the current internal political and economic issues at home, and the Canadian public demand for a sharply reduced role in the world. The prevailing thought for interventionists is direct military missions are just, as long as the cause is just, no matter the dangers or risk associated with the mission. Global economic volatility and the growth in the intensity of regional conflicts, particularly in Asia and the Middle East, are certain to further dampen the enthusiasm of Canadian voters for costly foreign interventions, no matter how ‘just’ the cause is.

As of 2011, $7.5 billion has been spent on combat operations and $1.2 billion on development assistance. The mission in Libya cost nearly $350-million—seven times what Defence Minister Peter MacKay told Canadians it would cost. War weariness as a result of Afghanistan and Libya are being blamed for Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s reluctance to send a direct Canadian military mission to Mali. The reality is Canada cannot afford to station troops given the defense cuts under the new federal budget. Base closings, personnel cuts and scaled-back defense contracts are the Harper government’s prerogative for the Canadian Forces in the foreseeable future.

Even if Prime Minister Harper allocated extra funds for an intervention in Mali, our own domestic institutions are in need of immediate improvements. Aboriginals continue to have a great need for health and education funding, there is a lack of access to clean drinking water and a rampant issue of substance abuse. Furthermore, nearly 1 million young Canadians aren’t working or in school and Canada’s wage gap is at a record high. How can interventionists in Canada loudly and passionately urge military intervention in Mali, when the Canadian government does not have adequate funds to deal with domestic issues?

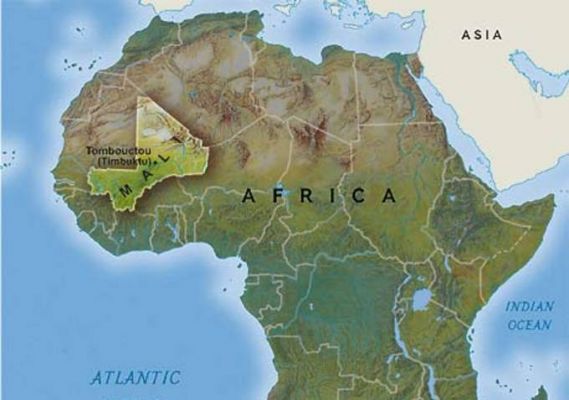

Mali is a sparsely-populated desert country that sprawls over a large expanse of northwest Africa. The living conditions are some of the harshest in the world. The northern region has for years been the object of fighting among tribal groups hostile to the ruling powers in the south. These conditions are less than optimal for the Canadian Forces. In Iraq, the land journey to Baghdad was often met with fierce sand storms that caused American military vehicles to break down before they even begun the several-hundred-kilometer journey to Baghdad. It took days of the most complex logistics to cross the hostile desert. Canadian military capabilities are a far cry from American military capabilities, and could not efficiently handle the physical terrain in Mali. The desert is a major impediment to Canada’s chance of success in Mali and Canadian troops are hardly experts at battling guerrilla fighters in the middle of the Sahara.

Ironically, Fowler’s acknowledges that the Libya intervention inadvertently caused havoc to spread across the region by making possible the wholesale looting of Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi’s arsenals. This is yet another example that good intentions have little to do with positive outcomes.

Perhaps more critical is Flower’s failure to realize that the overstretching of resources causes an isolationist backlash. Not to mention the hatred that aggressive foreign policy breeds towards the aggressor. Involving ourselves in a large scale operation in Mali could have a much greater cost in blood and treasure, as is the case in Afghanistan. If Canada rebalances at home first, Canadian leadership can again prove crucial for international peace and prosperity.

The forces of mass communications and economic integration have weakened the power of the Canadian state. Nation-building should be a key priority of the Harper government. The government should focus on a cost-sensitive approach to foreign policy, domestic jobs and re-establishing the middle class. Excessive zeal in foreign policy is not what Canada needs.

Canada has provided Mali with hundreds of millions of dollars in aid over the past 40 years, while Canadian Special Forces troops helped train Malian government soldiers up until last year. In 2012, alone, the Canadian government contributed $57.5-million to help those affected by the food crisis―a very generous development program. Canadian assistance through equipment, intelligence, and logistical support are options the Harper government could consider. With two interventions aside, it is now time to learn from our mistakes, adapt to changing circumstances, innovate where possible, partner when necessary, and play to our core strengths. An ideologically driven foreign policy is a luxury Canada cannot afford to have.