Winston Churchill famously said, “The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.” 61 years after his term as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, it’s in the hand of the average voter to decide the fate of his country. How is the decision going to be made? A simple referendum!

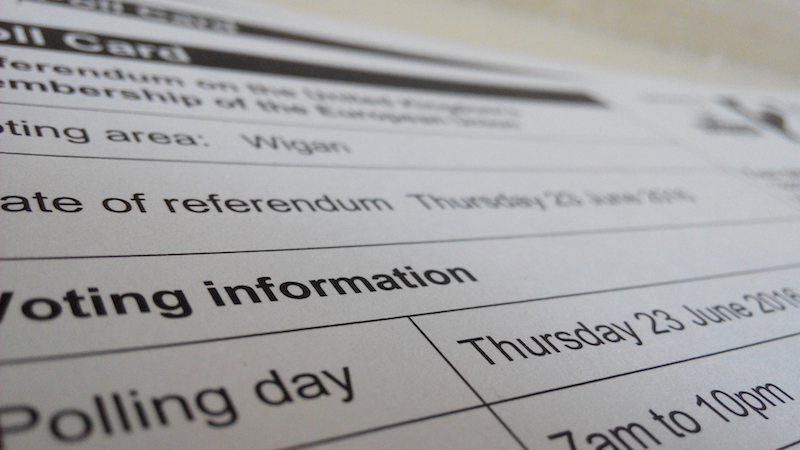

With the EU referendum taking place today, the debate both within the UK and abroad is at a climax. Predictably, the issues at hand range from economics and sovereignty to immigration and border control. Though the results won’t be released until tomorrow morning, the debate has also given rise to another important question: are referendums ideal for making political decisions in the first place?

The controversy around referendums is neither new nor unknown. The concept of direct democracy dates back to the time of Athenian democracy, and so does the debate. From Plato and Rousseau to Madison and Patten, philosophers and politicians alike have had their say on direct democracy.

Julian Critchley described referendums as the “favourite form of plebiscitary democracy of Mussolini and Hitler.” Margaret Thatcher, quoting Clement Attlee, meanwhile called them “a device of dictators and demagogues.”

On the Brexit referendum, even scientists such as Richard Dawkins have been critical: “it is an outrage that people as ignorant as me are being asked to vote. This is a complicated matter of economics, politics, history, and we live in a representative democracy not a plebiscite democracy. You could make a case for having plebiscites on certain issues – I could imagine somebody arguing for one on fox hunting, for example – but not on something as involved as the European Union. This should be a matter for parliament.”

Let’s take a look at the arguments for and against referendums.

What is a referendum?

Referendum, a gerund for the Latin verb refero (bringing back), means bringing the question back to the people. In modern day democracies, it is a method of referring a question or set of questions directly to an entire electorate. Simply put, a referendum is a vote consisting of a simple “Yes” or “No” answer to a question. Whichever side gets more than half of all the votes is considered to have won.

Referendums in the UK

Since 1973, there have been eleven referendums in the UK, only two of which have engaged the entire country. The first was in 1975, on Britain’s membership in the European Economic Community (with a vote to remain a member), and the second in 2011, which saw the rejection of the proposed “alternative vote” (AV) electoral system. The 2014 Scottish referendum, the most recent to take place within the UK, led to a “No” vote on Scottish independence.

Arguments for Referendums

Perhaps the principal argument in favour of referendums is that they offer a very real form of direct democracy. Indeed, direct democracy has a natural appeal: why not skip the party politics, lobbyist tactics, and legislators’ self-interest and put the decision in the hand of the voter? Since the average voter would face the impact of the political decision, would he or she not be best suited to make it in the first place?

Referendums lead to a rise in public participation. National elections, depending on jurisdiction, usually happen every four to five years, and referendums allow for the political participation in the interim. They also give citizens the incentive to inform themselves about politics.

And given the selection boils down to a simple “yes” or “no,” referendums offer clear answers to political questions. They’re particularly useful for resolving political tensions, such as cases of division within the governing party. This was true for the 1975 referendum, when the ruling Labour government had been split over Britain’s membership in the European Economic Community

Overall, the arguments in favour of referendums emphasise the democratic process, public participation and the ability of referendums to end political tensions.

Arguments Against Referendums

A key tension in the debate on referendums is whether they’re too demanding for the ordinary voter, whose expertise in economics, politics and policy is bound to be limited. Voters may lack the capacity or knowledge to make informed decisions on complex matters, or they may be influenced by unrelated arbitrary factors.

Though referendums can break down complicated matters into simple yes/no questions, public policy debates are quite often multifaceted. Is it really fair to boil the issue down to a simple sentence?

Most modern governments operate as representative democracies, where voters choose politicians to represent them in the decision-making process. As such, referendums can undermine the role of representatives and, by extent, representative democracy.

Referendums run the risk of letting elected representatives avoid having to take unpopular positions on controversial subjects. Political elites can also manipulate the timing of referendums to sway the outcome in their favour.

In contrast to the arguments for referendums that emphasize democratic participation and political resolve, those against referendums emphasize voter misinformation and the potential harms to representative democracy.

The Brexit Referendum

As this debate shows, referendums come with their virtues and vices. The Brexit referendum is no exception. The complex nature of the Britain’s relationship with the EU might be too much for the average voter to make a decision. But, in the end, it allows the public to make a choice they can ultimately live with.

In a recent interview, Prime Minister David Cameron insisted he had no regrets about calling for the EU referendum. He said, “As far as I am concerned this referendum should settle the matter.”

Cameron is right about the referendum: for better or for worse, the EU referendum has the power to settle the debate. In the little time that’s left, British voters should deliberate carefully about what the consequences of a Brexit would be. Let’s hope the outcome is for the better.

Photo: “Brexit or Remain?” (2016), by Abi Begum via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.