Power and politics are defined along ethnic lines in Afghanistan. It is the fact of Afghanistan’s modern power arrangement. Each ethnicity has its share. And, if the Taliban, predominately coming from the Pashtun ethnic group, are to take any share of post-2014 power bargain, who is going to pay for it?

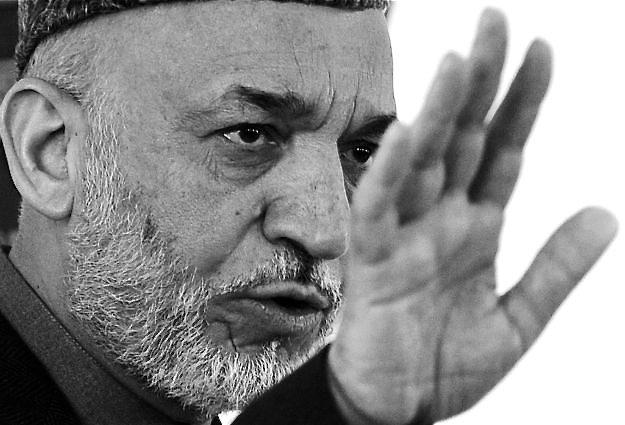

President Karzai calls the Taliban his “disenchanted brothers.” He knew their commanders from the days of Jihad against the Soviets. He supported them in the early 90s, to the point that he was one of the candidates to represent the Taliban in the United Nations during their UN bide to gain Afghanistan’s seat from the incumbent Islamic Republic of Afghanistan led by President Burhanuddin Rabbani.

In 2001, when he became the head of the Afghanistan Interim Administration in Kabul, he declared complete amnesty to the Taliban, from their leadership to their foot soldiers, though he had no legal authority to do so. Later, during his presidency, he didn’t put forth any real plan to eliminate the Taliban. Instead, he fought to bring the Taliban inside the government though the Afghanistan National Independent Peace and Reconciliation Commission, costing him allies and making him new enemies.

Karzai’s rhetoric and actions changed when the Taliban opened their office in Doha on June 15, 2013. The opening of the Taliban office was facilitated by the US, Pakistan and Qatari governments. Karzai realized that peace might be possible with the Taliban. All of a sudden, from a man of peace, he became the first one to reject it.

This was the first time Karzai and his team realized the deep potential consequences of peace with the Taliban. If the Taliban were to gain a share of the power in Kabul, someone else would have to step down. Obviously, other ethnicities, Tajiks, Hazaras and Uzbeks, would not do it; they might even fight for it. It would be President Karzai’s circle of trustees; the governing Pashtun elite, who would have to share the power that they have enjoyed for the last 12 years. Realizing this, no wonder President Karzai cynically sabotaged the initial talks with the Taliban in Doha.

Karzai halted US-Afghanistan Bilateral Security Agreement talks putting the US officials and Afghanistan’s national interest in limbo. He mobilized his supporters within the tribal elders organizing the traditional Grand Council, known as Loya Jirga, to discuss the future of Afghanistan after 2014. Keep in mind that Afghanistan is going to a presidential election in 2014 and Karzai cannot participate in it due to the constitutional two-term limit. What he will discuss there is unknown, although Grand Council has always served him well. It has been his source of legitimately bypassing Afghanistan’s constitution and secondary laws.

By making a mess of Afghanistan’s 2014 transition, Karzai is pressuring the US to ensure that the Taliban won’t replace his team. He knows that he can put pressure on the US and the Alliance forces to bend to his conditions as they are looking for a quick solution to the war in Afghanistan before their withdrawal.

For the US, it would be sensible to find a niche for Karzai and his team in some kind of deal with the Taliban before reaching out to other ethnic groups. If the Taliban wants to participate in any kind of political settlement, it shouldn’t be at the cost of other ethnic groups. Balanced ethnic political participation has been key for the partial stability of Afghanistan. Any attempt to change this will be a recipe for another bloody civil war.