Although it is a democratic country and a member of the G20, India has been labeled as one of the most dangerous places for women to live in. It is because of embedded patriarchal norms, corrupt policing, institutional sexism, and ultraconservative communities that India’s flaws continue to be highlighted in mainstream media. Insecurity of women is rising in multifaceted ways: from rape and honour killings to human trafficking. Destroying the tradition of gender-based violence seems to be an impossible process. Spectators must understand that India’s culture of impunity is one of the major root causes for the survival of gender-based violence in India during peacetime.

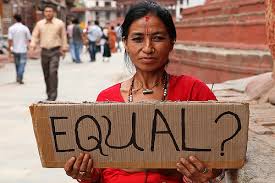

A well-known case that most people are familiar with occurred on 16 December 2012. A medical student was raped by six men on a public bus that was traveling on main roads and shortly after she passed away due to severe wounds. In response, civilians took to the streets and voiced their concerns and demanded the abolishment of impunity. Canadians also took part in protests in Toronto by marching in silence to the Indian consulate and handing over a signed petition.

Protests resulted in the implementation of stronger laws dedicated to enforcing harsher punishment for committing sexual violence against females. Sadly, actions such as these do not prevent civilians from following in the footsteps of former perpetrators and the August 2013 case is an example of this.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/protest-in-india-over-wom-005.jpg ” captiontext=””]

The Scope of Gender-Based Discrimination

There are over 2.5 million cases in which women and girls have fallen victim to numerous forms of sexual violence, and the rate at which these cases are dealt with by the judicial system is sadly occurring at an inefficient pace. Also, the police handle such cases as insignificant thus suspects can easily get away with committing horrendous crimes against females. The conviction rate has decreased from 46% to 26% within the past 41 years

Apart from India’s rape culture, traditions in patriarchal India are also increasing women’s insecurity. Many such cases revolve around conflict over dowry payments during the time that a bride marries a groom. An estimated 8,233 women have been reported killed as a result of dowry-related disputes. Though this practice is illegal, it continues to persist.

Another form of violence committed against females is honour killings. They often occur when a female has dishonoured the family by having a relationship with a male, escaping from an abusive family after marriage, or getting married without permission. A horrific example of unjustifiably committing an honour killing occurred when a 14 year old escaped from the clutches of an abusive family after marriage and moved in with a former boyfriend. The young girl’s brother decapitated her and justified his action by declaring that she had to be punished.

The Challenges of Contemporary India

The Indian government wants to be seen by the public as an effective force that is able to deal with such crimes. It is for this reason that the government passed laws related to the securitization of females in March 2013. The laws address issues that are of the utmost importance: there is higher sentencing, as well as the death penalty, for rape-related crimes; police officers and other public servants are no longer protected if they fail to register complaints; and stringent laws against stalking, voyeurism, acid violence, and disrobing are now in effect.

India has taken the first step by creating and implementing these laws, but traditional views that cause gender-based discrimination will still continue to dominate its society. An efficient technique to reduce gender-based violence should begin at the institutional level since sexism is unfortunately thriving within a criminal justice system, which is lagging in transparency and accountability. Imposing strict repercussions and preventive strategies will reduce the rate of crimes committed against women and girls. The police force is lacking in numbers and their priority appears to be to serve and protect the elite. There is also a shortage of judges. Another issue is the way in which police officers blame the victims by commenting on the type of clothes they wear – a “you brought it on yourself” mentality is thriving. Even those who visit public spaces, such as pubs, are labeled as immoral and therefore it is okay to violate their rights. The biggest issue, however, is the lower status of women in Indian society.

It is crucial to counter traditional ways of thinking because the unfortunate truth is that violence against females is a collective issue that many Indians accept – collective consciousness must be molded so that it is compatible with democratic principles. To combat these issues the criminal justice system must be reformed and civilians must continue to voice their demands for gender equality. Female insecurity is a multi-level problem that cannot be fixed from simply imposing laws.