Over the last decade, world politics have come to be dominated by so-called ‘strongmen’ leaders. That young voters even in the most established democracies of the world are losing faith in the democratic process is a troubling idea. Increasingly, these same voters yearn for leaders who can govern with a strong mandate to ‘fix’ the broken state of politics in their country. This new wave of populism driven by voter fear, anger and frustration is increasingly manifesting itself in the political rhetoric of leaders of many democracies. United States elected the businessman Donald Trump as its 46th President, a man described by the media as someone who resembles a dictator in his governing style. Trump came to power on the back of his pre-election promise to take a tough stance against immigration and international trade and his penchant for pursuing an isolationist foreign policy. Trump’s authoritarian tendencies stem from his lack of respect for the institutions of democracy and a free press. Several democratic leaders, whether it is Shinzo Abe of Japan or Narendra Modi of India, are accused of being authoritarian leaders with a penchant for centralizing power and ruling with an iron fist. Are these democratically elected strongmen leaders cut from the same cloth as those like Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin who are products of systemic dictatorships?

Although the media would like to portray all strongmen leaders as authoritarian, power hungry, egotistic control freaks and bombastic in their pronouncements, there is a world of difference between those leaders at the head of democracies versus those who are unelected and rule over dictatorships. First, even if Trump’s presidency ends up in unmitigated disaster, he can only run for office for two terms as president, at the end of which he would have to leave office as per constitutionally mandated term limits. Moreover, there are limits to his Presidential powers, with checks and balances stemming from the powers vested in Congress and the judiciary, the other two pillars of government, although both houses of Congress are currently dominated by his own Republican party. The fact that the Muller investigation is still actively pursuing the investigation into Trump’s alleged collusion with Russia over its meddling in the 2016 U.S. elections is a testament to the independence of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). It shows that even a strong and powerful president cannot subvert the constitutional functions of a government institution that reports to his own Justice Department. Trump also faces a mid-term election in November 2018 in which the party in power has traditionally performed poorly, and if the Republicans lose their majority, this could place an additional check on Trump’s aspirations, affecting his popularity in opinion polls. Moreover, any indictments in the Mueller probe could potentially lead to impeachment hearings in Congress, putting more pressure on Trump and his presidency. Any bad decisions he makes with respect to U.S. policy on Russia and North Korea could invite more criticism and roil the state of domestic politics.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi rose to power through a thumping majority in general elections held in May 2014 and is described as a leader with an authoritarian streak and a dictatorial governing style. Modi is known to make decisions through a close coterie of trusted bureaucrats, often ignoring advice from his own cabinet ministers. He has been accused of muzzling the media and erecting roadblocks against press freedom. His party has also been accused of turning a blind eye to so called cow vigilantism and deadly attacks on Muslims involved in cattle trading, as his Hindu nationalist BJP party considers cows sacred to Hindus. Despite his widespread popularity and his remarkable winning streak in elections held for the state legislative assemblies, Modi faces several headwinds as he goes into the next general elections slated for mid-2019. The opposition parties who hope to dethrone Modi have been coming together to form a united coalition to defeat him in the election. Even though large sections of the Indian broadcast media have been muted in their criticism of Modi, he faces a cacophony of voices critical of his policies on social media and online newspapers. Recently, Modi had to fight a no confidence vote in the Indian Parliament. He managed to win, but only after a day-long debate in Parliament about the performance of his government. Most early pre-election polls indicate that Modi’s majority in Parliament could see a dent in the next election.

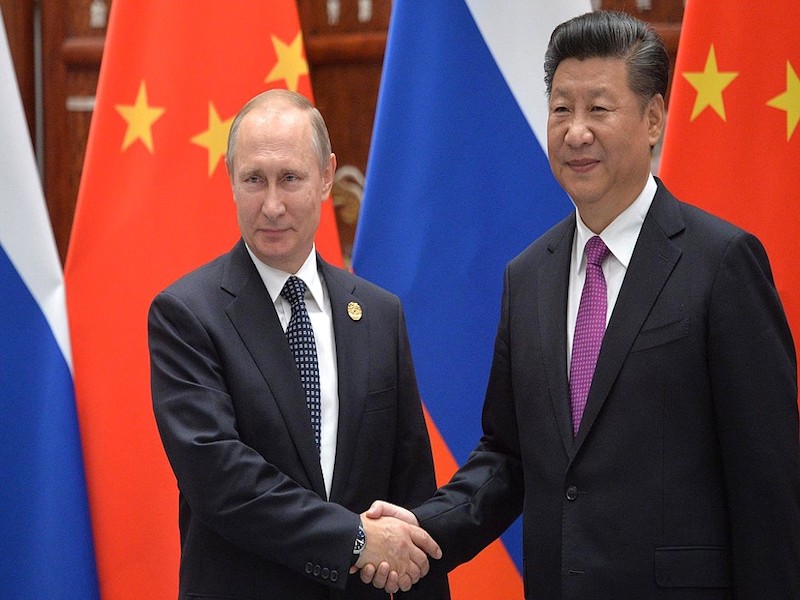

Unlike the two examples presented above, leaders in China and Russia do not have to subject themselves to the scrutiny that democratically elected leaders in the U.S. and India face within their own countries. President Xi Jinping, who came to power in 2012, has anointed himself as the ‘supreme leader’ of China for the foreseeable future. He now presides over one of the most authoritarian regimes in the world, one that places restrictions on freedom of expression and censors Internet content. Like the political philosophies of former Chairman Mao Xuedong and Deng Xiaoping, which form part of the Chinese constitution, President Xi’s political thoughts were enshrined in the constitution last year during the Communist Party Congress. During this 2017 Congress, Xi broke the ten-year rule that previous Chinese presidents like Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao had upheld since the end of the Deng and Mao eras.

Similarly, President Vladimir Putin has been in power in Russia now close to two decades and there are no signs that he will voluntarily relinquish office. The Russian state asserts almost total control over the media, engages in assassination attempts on foreign soil, launches invasions on its neighbours in violation of international law, and meddles in the elections of Western democracies. Even though Russia does hold presidential elections, unlike China where the president is appointed by the party congress, the Putin era is far from over.

During the Cold War, strongmen leaders were dictators who came to power through the barrel of the gun, through inheritance, or in a military coup. In the contemporary era, some strongmen leaders have risen to power through ‘free and fair’ elections in democracies. This does not mean they are entitled to stay in power forever like their counterparts in authoritarian states. The powers that these leaders wield in democracies are circumscribed by law; they must subject themselves to the will of the people and exit office when they are voted out in the next election cycle or adhere to term limits enshrined in the constitution. The tendency of some commentators to draw parallels between nationalistic leaders such as Xi and Modi is therefore misplaced and misleading because the two countries have radically different political systems – China is a dictatorship and India is described as a ‘noisy’ but functioning democracy. The two leaders may both exhibit authoritarian tendencies, but while Modi is held accountable through democratic elections, Xi has no such compulsions in clinging on to power. He does not have to pay heed to the political aspirations of his people and legitimatizing his rule through electoral politics. While authoritarian leaders like Trump and Modi can be punished by their voters if they overstep their boundaries in governance, Xi and Putin have unbridled authority in prolonging their rule if they wish to do so. Not all strongmen in world politics are cut from the same cloth. That indeed is the key missing element in the current debate about the rise of authoritarianism in Western democracies.

Photo: Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping at G20 Summit in Hangzhou (2016), by en.kremlin.ru via en.kremlin.ru. Licensed under CC0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.