Canada has a long history of involvement in various issues pertaining to nuclear technology. As a member of the Manhattan Project along with the US and Britain, Canada actively contributed scientific expertise and material resources to develop the technology that led to the first nuclear weapon. However, Ottawa made a conscious decision following the end of WWII to denounce nuclear weapons and promised not to pursue a “Canadian bomb”, despite having the capability to do so. Since then, Canada has adopted an aggressive policy of non-proliferation and disarmament, and has signed on to every major nuclear treaty to which the state could be party to.

Canada has a long history of involvement in various issues pertaining to nuclear technology. As a member of the Manhattan Project along with the US and Britain, Canada actively contributed scientific expertise and material resources to develop the technology that led to the first nuclear weapon. However, Ottawa made a conscious decision following the end of WWII to denounce nuclear weapons and promised not to pursue a “Canadian bomb”, despite having the capability to do so. Since then, Canada has adopted an aggressive policy of non-proliferation and disarmament, and has signed on to every major nuclear treaty to which the state could be party to.

In the diplomatic realm, Canada has projected itself as a stalwart opponent to nuclear weapons while also being a strong advocate for peaceful nuclear power. The technological and resource advantage Canada enjoyed through its participation in wartime nuclear research ensured the state a leading role in the global nuclear regime, and Canada has used its position to advance its policy of nuclear disarmament. Ottawa’s official policy on nuclear weapons is based on three “pillars”, which includes supporting and promoting the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) to stop the spread of nuclear weapons, advocating for a Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), and leading the way in negotiating a Fissile Materials Cut-off Treaty (FMCT) to ban the production of fissile materials for use in nuclear weapons.

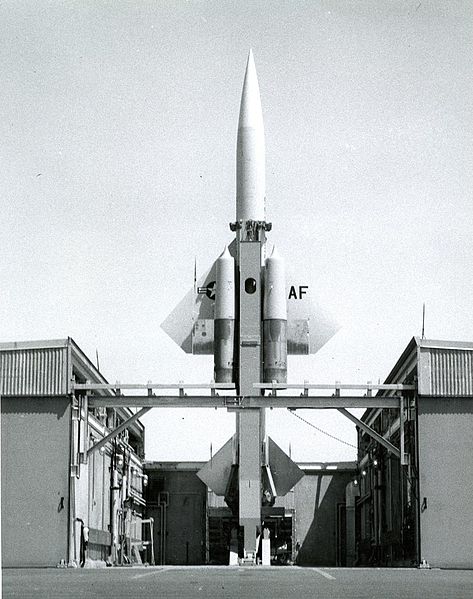

However, while Canada has played a leading role in the international community in preventing the proliferation of nuclear warheads, Ottawa’s obligations to NATO appear to contradict Canada’s diplomatic efforts. Between the period of 1963 to 1984, Canada was actively involved in supplying NATO’s nuclear strike capabilities, stationing Canadian missiles and aircraft in Western Europe and equipping them with American nuclear warheads. American warheads were also provided to Canadian forces on home soil, which was part of NORAD’s nuclear deterrence policy. While Canada absolved itself of all nuclear weapons in 1984 as the Cold War entered its waning years, Ottawa’s continued commitments to NATO ensures a degree of consent to the idea of nuclear deterrence, even if this support is tacit and indirect.

Despite the evolving face of international security over the last two decades and the reduced threat of nuclear war, NATO remains a nuclear alliance. Unlike during the Cold War, however, NATO asserts a right to retain nuclear weapons for deterrence and defensive purposes only, rather than asserting its right to possess a first strike capability. The Organization’s latest Strategic Concept, released in November, 2010, states that “[NATO] commits to the goal of creating the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons – but reconfirms that, as long as there are nuclear weapons in the world, NATO will remain a nuclear Alliance.” This statement, and the document as a whole, was approved by all NATO members, indicating that Canada to some extent agrees to NATO’s assertion that nuclear weapons are necessary for mutual security and deterrence. Of course, to some, this contradicts Canada’s diplomatic approach, as Ottawa projects itself as an opponent of nuclear arms while quietly accepting NATO’s pro-nuclear position and thus placing itself under the protection of the Alliance’s nuclear umbrella.

However, Canada’s nuclear policies with regards to NATO and diplomacy should not be criticized as being hypocritical but should instead be regarded as being realistic. NATO takes into account the existence of nuclear weapons in the world today and rationally responds by asserting the need for a nuclear deterrent in order to ensure collective security for its members. On the other hand, a key component of NATO’s policy towards nuclear weapons is to “[contribute] actively to arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament,” and the Alliance seeks to “create the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons.” These attitudes are entirely in line with Canada’s own diplomatic efforts, and Canada has been instrumental in pushing for reforms to NATO’s Cold War nuclear strategies. The signing of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) between the US and Russia in 2010 and its subsequent ratification was praised by NATO as being an important step in nuclear disarmament, which indicates that there is more agreement than disagreement between the Alliance and Canada in respect to nuclear weapons.

If Canada has been successful in promoting disarmament through diplomacy, but also enjoys the protection of NATO’s nuclear deterrence, is there any strategic purpose in changing this two-track approach? The obvious answer seems to be no, considering that Canada has had little resistance in exerting its diplomatic influence and at the same time has enhanced its security situation through its membership in NATO. Still, Canada has a strategic interest in reducing NATO’s nuclear stockpile, but in conjunction with reducing the overall global supply of nuclear weapons. A world without nuclear weapons may be the ultimate goal for Canada, but considering there is still significant progress that needs to be made before that ever happens, Canada will continue to employ a two-track approach to nuclear weapons by both aggressively advocating nuclear disarmament while accepting the realities of the current world order, in which nuclear deterrence is a necessary element of collective security.